Matsuo Basho's "Narrow Road to the Deep North"

Tr. by Nobuyuki Yuasa

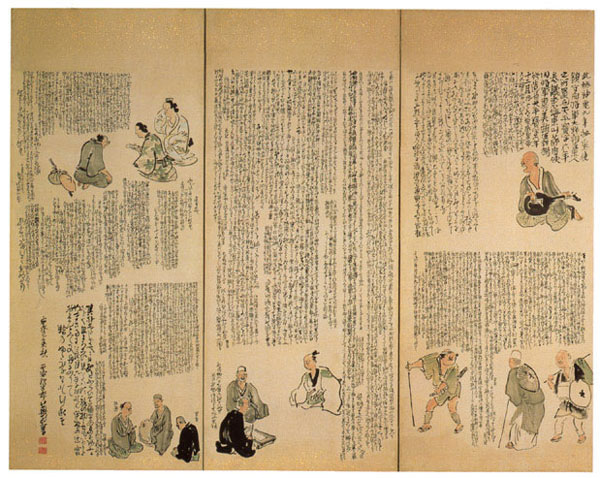

「奥の細道図屏風」与謝蕪村 (1716-1783)

Matsuo Basho's "Narrow Road to the Deep North" with illustrations (J., haiga) by Yosa Buson

(Important Cultural Property). Edo period, dated 1779.

http://syuweb.kyohaku.go.jp/ibmuseum_public/index.php?app=shiryo&mode=detail&language=en&data_id=980&list_id=3701

http://www.emuseum.jp/detail/100981?d_lang=en&s_lang=en&word=&class=&title=&c_e=®ion=&era=&cptype=&owner=&pos=273&num=4&mode=detail¢ury=

Station 1 - Prologue

Days and months are the travellers of eternity. So are the years that pass by. Those who steer a boat across the sea, or drive a horse over the earth till they succumb to the weight of years, spend every minute of their lives travelling. There are a great number of the ancients, too, who died on the road. I myself have been tempted for a long time by the cloud-moving wind- filled with a strong desire to wander.

It was only toward the end of last autumn that I returned from rambling along the coast. I barely had time to sweep the cobwebs from my broken house on the River Sumida before the New Year, but no sooner had the spring mist begun to rise over the field than I wanted to be on the road again to cross the barrier-gate of Shirakawa in due time. The gods seem to have possessed my soul and turned it inside out, and the roadside images seemed to invite me from every corner, so that it was impossible for me to stay idle at home.

Even while I was getting ready, mending my torn trousers, tying a new strap to my hat, and applying moxa to my legs to strengthen them, I was already dreaming of the full moon rising over the islands of Matsushima. Finally, I sold my house, moving to the cottage of Sampu, for a temporary stay. Upon the threshold of my old home, however, I wrote a linked verse of eight pieces and hung it on a wooden pillar.

The starting piece was:

Behind this door

Now buried in deep grass

A different generation will celebrate

The Festival of Dolls.

Station 2 - Departure

It was early on the morning of March the twenty-seventh that I took to the road. There was darkness lingering in the sky, and the moon was still visible, though gradually thinning away. The faint shadow of Mount Fuji and the cherry blossoms of Ueno and Yanaka were bidding me a last farewell. My friends had got together the night before, and they all came with me on the boat to keep me company for the first few miles. When we got off the boat at Senju, however, the thought of three thousand miles before me suddenly filled my heart, and neither the houses of the town nor the faces of my friends could be seen by my tearful eyes except as a vision.

The passing spring

Birds mourn,

Fishes weep

With tearful eyes.

With this poem to commemorate my departure, I walked forth on my journey, but lingering thoughts made my steps heavy. My friends stood in a line and waved good-bye as long as they could see my back.

Station 3 - Soka

I walked all through that day, ever wishing to return after seeing the strange sights of the far north, but not really believing in the possibility, for I knew that departing like this on a long journey in the second year of Genroku I should only accumulate more frosty hairs on my head as I approached the colder regions. When I reached the village of Soka in the evening, my bony shoulders were sore because of the load I had carried, which consisted of a paper coat to keep me warm at night, a light cotton gown to wear after the bath, scanty protection against the rain, writing equipment, and gifts from certain friends of mine. I wanted to travel light, of course, but there were always certain things I could not throw away either for practical or sentimental reasons.

Station 4 - Muronoyashima

I went to see the shrine of Muronoyashima. According to Sora, my companion, this shrine is dedicated to the goddess called the Lady of the Flower-Bearing Trees, who has another shrine at the foot of Mt.Fuji. This goddess is said to have locked herself up in a burning cell to prove the divine nature of her newly-conceived son when her husband doubted it. As a result, her son was named the Lord Born Out of the Fire, and her shrine, Muro-no-yashima, which means a burning cell. It was the custom of this place for poets to sing of the rising smoke, and for ordinary people not to eat konoshiro, a speckled fish, which has a vile smell when burnt

Station 5 - Nikko

I lodged in an inn at the foot of Mount Nikko on the night of March the thirtieth. The host of my inn introduced himself as Honest Gozaemon, and told me to sleep in perfect peace on his grass pillow, for his sole ambition was to be worthy of his name. I watched him rather carefully but found him almost stubbornly honest, utterly devoid of worldly cleverness. It was as if the merciful Buddha himself had taken the shape of a man to help me in my wandering pilgrimage. Indeed, such saintly honesty and purity as his must not be scorned, for it verges closely on the perfection preached by Confucius.

On the first day of April l3, I climbed Mt. Nikko to do homage to the holiest of the shrines upon it. This mountain used to be called Niko. When the high priest Kukai built a temple upon it, however, he changed the name to Nikko, which means the bright beams of the sun. Kukai must have had the power to see a thousand years into the future, for the mountain is now the seat of the most sacred of all shrines, and its benevolent power prevails throughout the land, embracing the entire people, like the bright beams of the sun. To say more about the shrine would be to violate its holiness.

It is with awe

That I beheld

Fresh leaves, green leaves,

Bright in the sun.

Mount Kurokami was visible through the mist in the distance. It was brilliantly white with snow in spite of its name, which means black hair.

Rid of my hair,

I came to Mount Kurokami

On the day we put on

Clean summer clothes.

--written by Sora

My companion's real name is Kawai Sogoro, Sora being his pen name. He used to live in my neighborhood and help me with such chores as bringing water and firewood. He wanted to enjoy the views of Matsushima and Kisagata with me, and also to share with me the hardships of the wandering journey. So he took to the road after taking the tonsure on the very morning of our departure, putting on the black robe of an itinerant priest, and even changing his name to Sogo, which means Religiously Enlightened. His poem, therefore, is not intended as a mere description of Mount Kurokami. The last determination to persist in his purpose.

After climbing two hundred yards or so from the shrine, I came to a waterfall, which came pouring out of a hollow in the ridge and tumbled down into a dark green pool below in a huge leap of several hundred feet. The rocks of the waterfall were so carved out that we could see it from behind, though hidden ourselves in a craggy cave. Hence its nickname, See-from-behind.

Silent a while in a cave,

I watched a waterfall

For the first of

The summer observances

Station 6 - Nasu

A friend was living in the town of Kurobane in the province of Nasu. There was a wide expanse of grass-moor, and the town was on the other side of it. I decided to follow a shortcut which ran straight for miles and miles across the moor. I noticed a small village in the distance, but before I reached it, rain began to fall and darkness closed in. I put up at a solitary farmer's house for the night, and started again early next morning. As I was plodding though the grass, I noticed a horse grazing by the roadside and a farmer cutting grass with a sickle. I asked him to do me the favor of lending me his horse. The farmer hesitated for a while, but finally with a touch of sympathy in his face, he said to me, 'There are hundreds of cross-roads in the grass-moor. A stranger like you can easily go astray. This horse knows the way. You can send him back when he won't go any further.' So I mounted the horse and started off, when two small children came running after me. One of them was a girl named kasane, which means manifold. I thought her name was somewhat strange but exceptionally beautiful.

If your name, Kasane,

Means manifold,

How befitting it is also

For a double-flowered pink.

By and by I came to a small village. I therefore sent back the horse, with a small amount of money tied to the saddle.

Station 7 - Kurobane

I arrived safely at the town of Kurobane, and visited my friend, Joboji, who was then looking after the mansion of his lord in his absence. He was overjoyed to see me so unexpectedly, and we talked for days and nights together. His brother, Tosui, seized every opportunity to talk with me, accompanied me to his home and introduced me to his relatives and friends. One day we took a walk to the suburbs. We saw the ruins of an ancient dog shooting ground, and pushed further out into the grass-moor to see the tomb of Lady Tamamo and the famous Hachiman Shrine, upon whose god the brave archer, Yoichi, is said to have called for aid when he was challenged to shoot a single fan suspended over a boat drifting offshore. We came home after dark.

I was invited out to the Komyoji Temple, to visit the hall in which was enshrined the founder of the Shugen sect. He is said to have travelled all over the country in wooden clogs, preaching his doctrines.

Amid mountains mountains of high summer,

I bowed respectfully before

The tall clogs of a statue,

Asking a blessing on my journey.

Station 8 - Unganji

There was a Zen temple called Unganji in this province. The priest Buccho used to live in isolation in the mountains behind the temple. He once told me that he had written the following poem on the rock of his hermitage with the charcoal he had made from pine.

This grassy hermitage,

Hardly any more

Than five feet square,

I would gladly quit

But for the rain.

A group of young people accompanied me to the temple. they talked so cheerfully along the way that I reached it before I knew it. The temple was situated on the side of a mountain completely covered with dark cedars and pines. A narrow road trailed up the valley, between banks of dripping moss, leading us to the gate of the temple across a bridge. The air was still cold, though it was April.

I went behind the temple to see the remains of the priest Buccho's hermitage. It was a tiny hut propped against the base of a huge rock. I felt as if I was in the presence of the Priest Genmyo's cell or the Priest Houn's retreat. I hung on a wooden pillar of the cottage the following poem which I wrote impromptu.

Even the woodpeckers

Have left it untouched,

This tiny cottage

In a summer grove.

Station 9 - Sesshoseki

Taking leave of my friend in Kurobane, I started for the Murder Stone, so called because it kills birds and insects that approached it. I was riding on a horse my friend had lent me, when the farmer who led the horse asked me to compose a poem for him. His request came to me as a pleasant surprise.

Turn the head of your horse

Sideways across the field,

To let me hear

The cry of the cuckoo.

The Murder Stone was in the dark corner of a mountain near a hot spring, and was completely wrapped in the poisonous gas rising from it. There was such a pile of dead bees, butterflies, and other insects, that the real color of the ground was hardly discernable.

I went to see the willow tree which Saigyo celebrated in his poem when he wrote, "Spreading its shade over a crystal stream." I found it near the village of Ashino on the bank of a rice-field. I had been wondering in my mind where this tree was situated, for the ruler of this province had repeatedly talked to me about it, but this day, for the first time in my life, I had an opportunity to rest my worn-out legs under its shade.

When the girls had planted

A square of paddy-field,

I stepped out of

The shade of a willow tree.

Station 10 - Shirakawa

After many days of solitary wandering, I came at last to the barrier-gate of Shirakawa, which marks the entrance to the northern regions. Here, for the first time, my mind was able to gain a certain balance and composure, no longer victim to pestering anxiety, so it was with a mild sense of detachment that I thought about the ancient traveller who had passed through this gate with a burning desire to write home. This gate was counted among the three largest checking stations, and many poets had passed through it, each leaving a poem of his own making. I myself walked between trees laden with thick foliage with the distant sound of autumn wind in my ears and a vision of autumn tints before my eyes. There were hundreds and thousands of pure white blossoms of unohana in full bloom on either side of the road, in addition to the equally white blossoms of brambles, so that the ground, at a glance, seemed to be covered with early snow. According to the accounts of Kiyosuke, the ancients are said to have passed through this gate, dressed up in their best clothes.

Decorating my hair

With white blossoms of unohana,

I walked through the gate,

My only gala dress.

-- written by Sora

Station 11 - Sukagawa

Pushing towards the north, I crossed the River Abukuma, and walked between the high mountains of Aizu on the left and the three villages of Iwaki, Soma, and Miharu on the right, which were divided from the villages of Hitachi and Shimotsuke districts by a range of low mountains. I stopped at the Shadow Pond, so called because it was thought to reflect the exact shadow of any object that approached its shore. It was a cloudy day, however, and nothing but the grey sky was reflected in the pond. I called on the Poet Tokyu at the post town of Sukagawa, and spent a few days at his house. He asked me how I had fared at the gate of Shirakawa. I had to tell him that I had not been able to make as many poems as I wanted, partly because I had been absorbed in the wonders of the surrounding countryside and the recollections of ancient poets. It was deplorable, however, to have passed the gate of Shirakawa without a single poem worth recording, so I wrote:

The first poetic venture

I came across --

The rice planting-songs

Of the far north.

Using this poem as a starting piece, we made three books of linked verse.

There was a huge chestnut tree on the outskirts of this post town, and a priest was living in seclusion under its shade. When I stood there in front of the tree, I felt as if I were in the midst of the deep mountains where the poet Saigyo had picked nuts. I took a piece of paper from my bag, and wrote as follows:

"The chestnut is a holy tree, for the Chinese ideograph for chestnut is Tree placed directly below West, the direction of the holy land. The Priest Gyoki is said to have used it for his walking stick and the chief support of his house.

The chestnut by the eaves

In magnificient bloom

Passes unnoticed

By men of the world.

Station 12 - Asaka

Passing through the town of Hiwada, which was about five miles from the house of the Poet Tokyu, I came to the famous hills of Asaka. The hills were not very far from the highroad, and scattered with numerous pools. It was the season of a certain species of iris called katsumi. So I went to look for it. I went from pool to pool, asking every soul I met on the way where I could possibly find it, but strangely enough, no one had ever heard of it, and the sun went down before I caught even a glimpse of it. I cut across to the right at Nihonmatsu, saw the ancient cave of Kurozuka in a hurry, and put up for the night in Fukushima.

Station 13 - Shinobu

On the following morning I made my way to the village of Shinobu to look at the stone upon whose chequered face they used to dye a certain type of cloth called shinobu-zuri. I found the stone in the middle of a small village, half buried in the ground. According to the child who acted as a self-appointed guide, this stone was once on the top of a mountain, but the travellers who came to see it did so much harm to the cropsthat the farmers thought it a nuisance and thrust it down into the valley, where it rests now with its chequered face downward. I thought the story was not altogether unbelievable.

The busy hands

Of rice-planting girls,

Reminiscent somehow

Of the old dyeing technique.

Station 14 - Satoshoji

Crossing the ferry of Moon Halo, I came to the post town of Rapid's Head. The ruined house of the brave warrior Sato was about a mile and a half from this post town towards the foot of the mountains on the left. I pushed my way towards the village of Iizuka, and found a hill called Maruyama in the open field of Sabano. This was the site of the warrior's house. I could not refrain from weeping, when I saw the remains of the front gate at the foot of the hill. There was a lonely temple in the vicinity, and tombs of the Sato family were still standing in the graveyard. I wept bitterly in front of the tombstones of the two young wives, remembering how they had dressed up their frail bodies in armor after the death of their husbands. In fact I felt as if I were in the presence of the Weeping Tombstone of China.

I went into the temple to have a drink of tea. Among the treasures of the temple were the sword of Yoshitsune and the satchel which his faithful retainer, Benkei, had carried on his back.

Proudly exhibit

With flying banners

The sword and the satchel

This May festival day.

Station 15 - Iizuka

I stopped overnight at Iizuka. I had a bath in a hot spring before I took shelter at an inn. It was a filthy place with rough straw mats spread out on an earth floor. They had to prepare my bed by the dim light of the fire, for there was not even a lamp in the whole house. A storm came upon us towards midnight, and between the noise of the thunder and leaking rain and the raids of mosquitoes and fleas, I could not get a wink of sleep. Furthermore, an attack of my old complaint made me so ill that I suffered severely from repeated attacks while I rode on horseback bound for the town of Kori. It was indeed a terrible thing to be so ill on the road, when there still remained thousands of miles before me, but thinking that if I were to die on my way to the extreme north it would only be the fulfillment of providence, I trod the earth as firmly as possible and arrived at the barrier-gate of Okido in the province of Date.

Station 16 - Kasajima

Passing through the castle towns of Abumizuri and Shiroishi, I arrived at the province of Kasajima, where I asked the way to the mound of Lord Sanekata of the Fujiwara family. I was told that I must turn right in the direction of the villages of Minowa and Kasajima visible at the foot of the mountains in the distance, and that the mound was still there by the side of a shrine, buried in deep grass. I wanted to go that way, of course, but the muddy road after the early rain of the wet season and my own weakness stopped me. The names of the two villages were so befitting to the wet season with their echoes of raincoat and umbrella that I wrote:

How far must I walk

To the village of Kasajima

This endlessly muddy road

Of the early wet season?

I stopped overnight at Iwanuma.

Station 17 - Takekuma no Matsu

My heart leaped with joy when I saw the celebrated pine tree of Takekuma, its twin trunks shaped exactly as described by the ancient poets. I was immediately reminded of the priest Noin who had grieved to find upon his second visit this same tree cut down and thrown into the River Natori as bridge-piles by the newly-appointed governor of the province. This tree had been planted, cut, and replanted several times in the past, but just when I came to see it myself, it was in its original shape after a lapse of perhaps a thousand years, the most beautiful shape one could possibly think of for a pine tree. The poet Kyohaku wrote as follows at the time of my departure to express his good wishes for my journey:

Don't forget to show my master

The famous pine of Takekuma,

Late cherry blossoms

Of the far north.

The following poem I wrote was, therefore, a reply:

Three months after we saw

Cherry blossoms together

I came to see the glorious

Twin trunks of the pine.

Station 18 - Sendai

Crossing the River Natori, I entered the city of Sendai on May the fourth, the day we customarily throw fresh leaves of iris on the roof and pray for good health. I found an inn, and decided to stay there for several days. There was in this city a painter named Kaemon. I made special efforts to meet him, for he was reputed to be a man with a truly artistic mind. One day he took me to various places of interest which I might have missed but for his assistance. We first went to the plain of Miyagino, where fields of bush-clover were waiting to blossom in autumn. The hills of Tamada, Yokono, and Tsutsuji-ga-oka were covered with white rhododendrons in bloom. Then we went into the dark pine woods called Konoshita where even the beams of the sun could not penetrate. This darkest spot on the earth had often been the subject of poetry because of its dewiness - for example, one poet says that his lord needs an umbrella to protect him from the drops of dew when he enters it.

We also stopped at the shrines of Yakushido and Tenjin on our way home.

When the time came for us to say good-bye, this painter gave me his own drawings of Matsushima and Shiogama and two pairs of straw sandals with laces dyed in the deep blue of the iris. In this last appears most clearly perhaps the true artistic nature of this man.

It looks as if

Iris flowers had bloomed

On my feet --

Sandals laced in blue.

Station 19 - Tsubo no Ishibumi

Relying solely on the drawings of Kaemon which served as a guide, pushed along the Narrow Road to the Deep North, and came to the place where tall sedges were growing in clusters. This was the home of the famous sedge mats of Tofu. Even now it is the custom of the people of this area to send carefully woven mats as tribute to the governor each year.

I found the stone monument of Tsubo no Ishibumi on the ancient site of the Taga castle in the village of Ichikawa. The monument was about six feet tall and three feet wide, and the engraved letters were still visible on its surface through thick layers of moss. In addition to the numbers giving the mileage to various provinces, it was possible to read the following words: This castle was built upon the present site in the first year of Jinki (724) by General Ono no Azumabito dispatched to the Northern Provinces by His Majesty, and remodelled in the sixth year of Tempyohoji (762) by His majesty's Councillor and general Emi no Asakari, Governor of the Eastern and Northern Provinces.

According to the date given at the end of the inscription, this monument was erected during the reign of Emperor Shomu (724-49), and had stood here ever since, winning the increasing admiration of poets through the years. In this ever changing world where mountains crumble, rivers change their courses, roads are deserted, rocks are buried, and old trees yield to young shoots, it was nothing short of a miracle that this monument alone had survived the battering of a thousand years to be the living memory of the ancients. I felt as if I were in the presence of the ancients themselves, and, forgetting all the troubles I had suffered on the road, rejoiced in the utter happiness of this joyful moment, not without tears in my eyes.

Station 20 - Shiogama

Stopping briefly at the River Noda no Tamagawa and the so-called Rock in the Offing, I came to the pine woods called Sue no Matsuyama, where I found a temple called Masshozan and a great number of tombstones scattered among the trees. It was a depressing sight indeed, for young or old, loved or loving, we must all go to such a place at the end of our lives. I entered the town of Shiogama hearing the ding-dong of the curfew. Above was the darkening sky, unusually empty for May, and beyond was the silhouette of Migaki ga Shima Island* not far from the shore in the moonlight.

The voices of the fishermen* dividing the catch of the day made me even more lonely, for I was immediately reminded of an old poem which pitied them for their precarious lives on the sea. Later in the evening, I had a chance to hear a blind minstrel singing to his lute. His songs were different from either the narrative songs of the Heike or the traditional songs of dancing, and were called Okujoruri (Dramatic Narratives of the Far North). I must confess that the songs were a bit too boisterous, when chanted so near my ears, but I found them not altogether unpleasing, for they still retained the rustic flavor of the past.

The following morning, I rose early and did homage to the great god of the Myojin Shrine of Shiogama. This shrine had been rebuilt by the former governor of the province* with stately columns, painted beams, and an impressive stone approach, and the morning sun shining directly on the vermillion fencing was almost dazzlingly bright. I was deeply impressed by the fact that the divine power of the gods had penetrated even to the extreme north of our country, and I bowed in humble reverence before the altar.

I noticed an old lantern in front of the shrine. According to the inscription on its iron window, it was dedicated by Izumi no Saburo in the third year of Bunji (1187). My thought immediately flew back across the span of five hundred years to the days of this most faithful warrior. His* life is certain evidence that, if one performs one's duty and maintains one's loyalty, fame comes naturally in the wake, for there is hardly anyone now who does not honor him as the flower of chivalry.

It was already close to noon when I left the shrine. I hired a boat and started for the islands of Matsushima. After two miles or so on the sea, I landed on the sandy beach of Ojima Island.

Station 21 - Matsushima

Much praise has already been lavished on the wonders of the islands of Matsushima. Yet if further praise is possible, I would like to say that here is the most beautiful spot in the whole country of Japan, and that the beauty of these islands is not in the least inferior to the beauty of Lake Dotei or Lake Seiko in China. The islands are situated in a bay about three miles wide in every direction and open to the sea through a narrow mouth on the south-east side. Just as the River Sekko in China is made full at each swell of the tide, so is this bay filled with the brimming water of the ocean and the innumerable islands are scattered over it from one end to the other. Tall islands point to the sky and level ones prostrate themselves before the surges of water. Islands are piled above islands, and islands are joined to islands, so that they look exactly like parents caressing their children or walking with them arm in arm. The pines are of the freshest green and their branches are curved in exquisite lines, bent by the wind constantly blowing through them. Indeed, the beauty of the entire scene can only be compared to the most divinely endowed of feminine countenances, for who else could have created such beauty but the great god of nature himself? My pen strove in vain to equal this superb creation of divine artifice.

Ojima Island where I landed was in reality a peninsula projecting far out into the sea. This was the place where the priest Ungo had once retired, and the rock on which he used to sit for meditation was still there. I noticed a number of tiny cottages scattered among the pine trees and pale blue threads of smoke rising from them. I wondered what kind of people were living in those isolated houses, and was approaching one of them with a strange sense of yearning, when, as if to interrupt me, the moon rose glittering over the darkened sea, completing the full transformation to a night-time scene. I lodged in an inn overlooking the bay, and went to bed in my upstairs room with all the windows open. As I lay there in the midst of the roaring wind and driving clouds, I felt myself to be in a world totally different from the one I was accustomed to. My companion Sora wrote:

Clear voiced cuckoo,

Even you will need

The silver wings of a crane

To span the islands of Matsushima.

I myself tried to fall asleep, supressing the surge of emotion from within, but my excitement was simply too great. I finally took out my notebook from my bag and read the poems given me by my friends at the time of my departure - Chinese poem by Sodo, a waka by Hara Anteki, haiku by Sampu and Dakushi, all about the islands of Matsushima.

I went to the Zuiganji temple on the eleventh. This temple was founded by Makabe no Heishiro after he had become a priest and returned from China, and was later enlarged by the Priest Ungo into a massive temple with seven stately halls embellished with gold. The priest I met at the temple was the thirty-second in descent from the founder. I also wondered in my mind where the temple of the much admired Priest Kenbutsu could have been situated.

Station 22 - Ishinomaki

I left for Hiraizumi on the twelfth. I wanted to see the pine tree of Aneha and the bridge of Odae on my way. So I followed a lonely mountain trail trodden only by hunters and woodcutters, but somehow I lost my way and came to the port of Ishinomaki. The port is located in a spacious bay, across which lay the island of Kinkazan, an old goldmine once celebrated as 'blooming with flowers of gold. There were hundreds of ships, large and small, anchored in the harbor, and countless streaks of smoke continually rising from the houses that thronged the shore. I was pleased to see this busy place, though it was mere chance that had brought me here, and began to look for a suitable place to stay. Strangely enough however, no one offered me hospitality. After much inquiring, I found a miserable house, and, spending an uneasy night, I wandered out again on the following morning on a road that was totally unknown to me. Looking across to the ford of Sode, the meadow of Obuchi and the pampas- moor of Mano, I pushed along the road that formed the embankment of a river. Sleeping overnight at Toima, where the long, swampish river came to an end at last, I arrived at Hiraizumi after wandering some twenty miles in two days.

Station 23 - Hiraizumi

It was here that the glory of three generations of the Fujiwara family passed away like a snatch of empty dream. The ruins of the main gate greeted my eyes a mile before I came upon Lord Hidehira's mansion, which had been utterly reduced to rice-paddies. Mount Kinkei alone retained its original shape. As I climbed one of the foothills called Takadate, where Lord Yoshitsune met his death, I saw the River Kitakami running through the plains of Nambu in its full force, and its tributary, Koromogawa, winding along the site of the Izumigashiro castle and pouring into the big river directly below my eyes. The ruined house of Lord Yasuhira was located to the north of the barrier-gate of Koromogaseki, thus blocking the entrance from the Nambu area and forming a protection against barbarous intruders from the north. Indeed, many a feat of chivalrous valor was repeated here during the short span of the three generations, but both the actors and the deeds have long been dead and passed into oblivion. When a country is defeated, there remain only mountains and rivers, and on a ruined castle in spring only grasses thrive. I sat down on my hat and wept bitterly till I almost forgot time.

A thicket of summer grass

Is all that remains

Of the dreams and ambitions

Of ancient warriors.

I caught a glimpse

Of the frosty hair of Kanefusa

Wavering among

The white blossoms of unohana

- written by Sora

The interiors of the two sacred buildings of whose wonders I had often heard with astonishment were at last revealed to me. In the library of sutras were placed the statues of the three nobles who governed this area, and enshrined in the so called Gold Chapel were the coffins containing their bodies, and under the all-devouring grass, their treasures scattered, their jewelled doors broken and their gold pillars crushed, but thanks to the outer frame and a covering of tiles added for protection, they had survived to be a monument of at least a thousand years.

Even the long rain of May

Has left it untouched -

This Gold Chapel

Aglow in the sombre shade.

Station 24 - Dewagoe

Turning away from the high road leading to the provinces of Nambu, I came to the village of Iwate, where I stopped overnight. The next day I looked at the Cape of Oguro and the tiny island of Mizu, both in a river, and arrived by way of Naruko hot spring at the barrier-gate of Shitomae which blocked the entrance to the province of Dewa. The gate-keepers were extremely suspicious, for very few travellers dared to pass this difficult road under normal circumstances. I was admitted after long waiting, so that darkness overtook me while I was climbing a huge mountain. I put up at a gate-keeper's house which I was very lucky to find in such a lonely place. A storm came upon us and I was held up for three days.

Bitten by fleas and lice,

I slept in a bed,

A horse urinating all the time

Close to my pillow.

According to the gate-keeper there was a huge body of mountains obstructing my way to the province of Dewa, and the road was terribly uncertain. So I decided to hire a guide. The gate-keeper was kind enough to find me a young man of tremendous physique, who walked in front of me with a curved sword strapped to his waist and a stick of oak gripped firmly in his hand. I myself followed him, afraid of what might happen on the way. What the gate-keeper had told me turned out to be true. The mountains were so thickly covered with foliage and the air underneath was so hushed that I felt as if I were groping my way in the dead of night. There was not even the cry of a single bird to be heard, and the wind seemed to breathe out black soot through every rift in the hanging clouds. I pushed my way through thick undergrowth of bamboo, crossing many streams and stumbling over many rocks, till at last I arrived at the village of Mogami after much shedding of cold sweat. My guide congratulated me by saying that I was indeed fortunate to have crossed the mountains in safety, for accidents of some sort had always happened on his past trips. I thanked him sincerely and parted from him. However, fear lingered in my mind some time after that.

Station 25 - Obanazawa

I visited Seifu in the town of Obanazawa. He was a rich merchant and yet a man of a truly poetic turn of mind. He had a deep understanding of the hardships of the wandering journey, for he himself had travelled frequently to the capital city. He invited me to stay at his place as long as I wished and tried to make me comfortable in every way he could.

I felt quite at home,

As if it were mine,

Sleeping lazily

In this house of fresh air.

Crawl out bravely

And show me your face,

The solitary voice of a toad

Beneath the silkworm nursery.

With a powder-brush

Before my eyes,

I strolled among

Rouge-plants.

In the silkworm nursery,

Men and women

Are dressed

Like gods in ancient times. -- Written by Sora

Station 26 - Ryushakuji

There was a temple called Ryushakuji in the province of Yamagata. Founded by the great priest Jikaku, this temple was known for the absolute tranquility of its holy compound. Since everybody advised me to see it, I changed my course at Obanazawa and went there, though it meant walking an extra seven miles or so. When I reached it, the late afternoon sun was still lingering over the scene. After arranging to stay with the priests at the foot of the mountain, I climbed to the temple situated near the summit. The whole mountain was made of massive rocks thrown together and covered with age-old pines and oaks. The stony ground itself bore the color of eternity, paved with velvety moss. The doors of the shrines built on the rocks were firmly barred and there was no sound to be heard. As I moved on all fours from rock to rock, bowing reverently at each shrine, I felt the purifying power of this holy environment pervading my whole being.

In the utter silence

Of a temple,

A cicada's voice alone

Penetrates the rocks.

Station 27 - Oishida

I wanted to sail down the River Mogami, but while I was waiting for fair weather at Oishida, I was told that the old seed of linked verse once strewn here by the scattering wind had taken root, still bearing its own flowers each year and thus softening the minds of rough villagers like the clear note of a reed pipe, but that these rural poets were now merely struggling to find their way in a forest of error, unable to distinguish between the new and the old style, for there was no one to guide them. At their request, therefore, I sat with them to compose a book of linked verse, and left it behind me as a gift. It was indeed a great pleasure for me to be of such help during my wandering journey.

Station 28 - Mogamigawa

The River Mogami rises in the high mountains of the far north, and its upper course runs through the province of Yamagata. There are many dangerous spots along this river, such as Speckled Stones and Eagle Rapids, but it finally empties itself into the sea at Sakata, after washing the north edge of Mount Itajiki. As I descended this river in a boat, I felt as if the mountains on both sides were ready to fall down upon me, for the boat was tiny one - the kind that farmers used for carrying sheaves of rice in old times - and the trees were heavily laden with foliage. I saw the Cascade of Silver Threads sparkling through the green leaves and the Temple called Sennindo standing close to the shore. The river was swollen to the brim, and the boat was in constant peril.

Gathering all the rains

Of May,

The River Mogami rushes down

In one violent stream.

Station 29 - Hagurosan

I climbed Mount Haguro on the third of June. Through the effort of my friend, Zushi Sakichi, I was granted an audience with the high priest Egaku, then presiding over this whole mountain temple acting as bishop. He received me kindly and gave me a comfortable lodging in one of the annexes in the South Valley.

On the following day, I sat with the priest in the main hall to compose some linked verse. I wrote:

Blessed indeed

Is this South Valley,

Where the gentle wind breathes

The faint aroma of snow.

I visited the Gongen shrine on the fifth. The founder of this shrine is the priest called Nojo, but no one knows exactly when he lived. Court Ceremonies and rites during the Years of Engi, however, mentions that there is a sacred shrine on Mount Sato in the province of Dewa. The scribe must have written Sato where he should have written Kuro in the province of Dewa. According to a local history book, the name of the province itself is derived from the fact that quantities of feathers were sent to the Emperor each year as a tribute from this province. Be that as it may, this shrine on Mount Haguro is counted among the three most sacred shrines of the north, together with the shrines on Mount Gassan and Mount Yudono, and is a sister shrine of the temple on Mount Toei in Edo. Here the doctrine of Absolute Meditation preached in the Tendai sect shines forth like the clear beams of the moon, and the Laws of Spiritual Freedom and Enlightenment illuminate as lamps in utter darkness. There are hundreds of houses where the priests practice religious rites with absolute severity. Indeed the whole mountain is filled with miraculous inspiration and sacred awe. Its glory will never perish as long as man continues to live on the earth.

Station 30 - Gassan

I climbed Mount Gassan on the eighth. I tied around my neck a sacred rope made of white paper and covered my head with a hood made of bleached cotton, and set off with my guide on a long march of eight miles to the top of the mountain. I walked through mists and clouds, breathing the thin air of high altitudes and stepping on slippery ice and snow, till at last through a gateway of clouds, as it seemed, to the very paths of the sun and moon, I reached the summit, completely out of breath and nearly frozen to death. Presently the sun went down and the moon rose glistening in the sky. I spread some leaves on the ground and went to sleep, resting my head on pliant bamboo branches. When, on the following morning, the sun rose again and dispersed the clouds, I went down towards Mount Yudono.

As I was still descending, I saw an old smithy built right on a trickling stream. According to my guide, this was where Gassan, a local swordsmith, used to make his swords, tempering them in the crystal-clear water of the stream. He made his swords with such skill and devotion that they became famous throughout the world. He must have chosen this particular spot for his smithy probably because he knew of a certain mysterious power latent in the water, just as indeed a similar power is known to have existed in the water of Ryosen Spring in China. Nor is the story of Kansho and Bakuya out of place here,* for it also teaches us that no matter where your interest lies, you will not be able to accomplish anything unless you bring your deepest devotion to it. As I sat reflecting thus upon a rock, I saw in front of me a cherry tree hardly three feet tall just beginning to blossom - far behind the season of course, but victorious against the heavy weight of snow which it had resisted for more than half a year. I immediatley thought of the famous Chinese poem about 'the plum tree fragrant in the blazing heat of summer' and of an equally pathetic poem by the priest Gyoson, and felt even more attached to the cherry tree in front of me. I saw many other things of interest in this mountain, the details of which, however, I refrain from betraying in accordance with the rules I must obey as a pilgrim. When I returned to my lodging, my host, Egaku, asked me to put down in verse some impressions of my pilgrimage to the three mountains, so I wrote as follows on the narrow strips of writing paper he had given me.

How cool it is,

A pale crescent shining

Above the dark hollow

Of Mount Haguro.

How many columns of clouds

Had risen and crumbled, I wonder

Before the silent moon rose

Over Mount Gassan.

Forbidden to betray

The holy secrets of Mount Yudono,

I drenched my sleeves

In a flood of reticent tears.

Tears rushed to my eyes

As I stepped knowingly

Upon the coins of the sacred road

Of Mount Yudono.

-- Written by Sora

Station 31 - Sakata

Leaving Mount Haguro on the following day, I came to the castle town called Tsuru-ga-oka, where I was received warmly by Nagayama Shigeyuki, a warrior, and composed a book of linked verse with him and Zushi Sakichi who had accompanied me all the way from Mount Haguro. Bidding them farewell, I again descended the River Mogami in a boat and arrived at the port of Sakata, where I was entertained by the physician named En'an Fugyoku.

I enjoyed the evening cool

Along the windy beach of Fukuura,

Behind me, Mount Atsumi

Still in the hot sun.

The River Mogami has drowned

Far and deep

Beneath its surging waves

The flaming sun of summer.

Station 32 - Kisagata

I had seen since my departure innumerable examples of natural beauty which land and water, mountains and rivers, had produced in one accord, and yet in no way could I suppress the great urge I had in my mind to see the miraculous beauty of Kisagata, a lagoon situated to the northeast of Sakata.* I followed a narrow trail for about ten miles, climbing steep hills, descending to rocky shores, or pushing through sandy beaches, but just about the time the dim sun was nearing the horizon, a strong wind arose from the sea, blowing up fine grains of sand, and rain, too, began to spread a grey film of cloud across the sky, so that even Mount Chokai was made invisible. I walked in this state of semi-blindness, picturing all sorts of views to myself, till at last I put up at a fisherman's hut, convinced that if there was so much beauty in the dark rain, much more was promised by fair weather.

A clear sky and brilliant sun greeted my eyes on the following morning, and I sailed across the lagoon in an open boat. I first stopped at a tiny island named after the Priest Noin to have a look at his retreat where he had stayed for three years, and then landed on the opposite shore where there was the aged cherry tree which Saigyo honored by writing 'sailing over the waves of blossoms. There was also a mausoleum of the Empress Jingu and the temple named Kanmanjuji. I was a bit surprised to hear of her visit here and left in doubt as to its historical truth, but I sat in a spacious room of the temple to command the entire view of the lagoon. When he hanging screens were rolled up, an extraordinary view unfolded itself before my eyes - Mount Chokai supporting the sky like a pillar in the south with its shadowy reflection in the water, the barrier-gate of Muyamuya just visible in the west, an endless causeway leading as far as Akita in the east, and finally in the north, Shiogoshi, the mouth of the lagoon with waves of the outer ocean breaking against it. Although little more than a mile in width, this lagoon is not the least inferior to Matsushima in charm and grace. There is, however, a remarkable difference between the two. Matsushima is a cheerful, laughing beauty, while the charm of Kisagata is in the beauty of its weeping countenance. It is not only lonely but also penitent, as it were, for some unknown evil. Indeed, it has a striking resemblance to the expression of a troubled mind.

A flowering silk tree

In the sleepy rain of Kisagata

Reminds me of Lady Seishi

In sorrowful lament.

Cranes hop around

On the watery beach of Shiogoshi

Dabbling their long legs

In the cool tide of the sea.

What special delicacy

Is served here, I wonder,

Coming to Kisagata

On a festival day

- Written by Sora

Sitting at full ease

On the doors of their huts,

The fishermen enjoy

A cool evening

- Written by Teiji

A poem for a pair of faithful osprey nesting on a rock:

What divine instinct

Has taught these birds

No waves swell so high

As to swamp their home?

- Written by Sora

Station 33 - Echigo

After lingering in Sakata for several days, I left on a long walk of a hundred and thirty miles to the capital of the province of Kaga. As I looked up at the clouds gathering around the mountains of the Hokuriku road, the thought of the great distance awaiting me almost overwhelmed my heart. Driving myself all the time, however, I entered the province of Echigo through the barrier-gate of Nezu, and arrived at the barrier-gate of Ichiburi in the province of Ecchu. During the nine days I needed for this trip, I could not write very much, what with the heat and moisture, and my old complaint that pestered me immeasurably.

The night looks different

Already on July the sixth,

For tomorrow, once a year

The weaver meets her lover.

The great Milky Way

Spans in a single arch

The billow-crested sea,

Falling on Sado beyond.

Station 34 - Ichiburi

Exhausted by the labor of crossing many dangerous places by the sea with such horrible names as Children-desert-parents or Parents- desert-children, Dog-denying or Horse-repelling, I went to bed early when I reached the barrier-gate of Ichiburi. The voices of two young women whispering in the next room, however, came creeping into my ears. They were talking to an elderly man, and I gathered from their whispers that they were concubines from Niigata in the province of Echigo, and that the old man, having accompanied them on their way to the Ise Shrine, was going home the next day with their messages to their relatives and friends. I sympathized with them, for as they said themselves among their whispers, their life was such that they had to drift along even as the white froth of waters that beat on the shore, and having been forced to find a new companion each night, they had to renew their pledge of love at every turn, thus proving each time the fatal sinfulness of their nature. I listened to their whispers till fatigue lulled me to sleep. When, on the following morning, I stepped into the road, I met these women again. They approached me and said with some tears in their eyes, 'We are forlorn travellers, complete strangers on this road. Will you be kind enough at least to let us follow you? If you are a priest as your black robe tells us, have mercy on us and help us to learn the great love of our Savior.' 'I am greatly touched by your words,' I said in reply after a moment's thought, 'but we have so many places to stop at on the way that we cannot help you. Go as other travellers go. If you have trust in the Savior, you will never lack His divine protection.' As I stepped away from them, however, my heart was filled with persisting pity.

Under the same roof

We all slept together,

Concubines and I -

Bush-clovers and the moon.

As I recited this poem to Sora, he immediately put it down on his notebook.

Crossing the so-called forty-eight rapids of the Kurobe River and countless other streams, I came to the village of Nago, where I inquired after the famous wisteria vines of Tako, for I wanted to see them in their early autumn colors though their flowering season was spring. The villagers answered me, however, that they were beyond the mountain in the distance about five miles away along the coastline, completely isolated from human abode, so that not a single fisherman's hut was likely to be found to give me a night's lodging. Terrified by these words, I walked straight into the province of Kaga.

I walked into the fumes

Of early-ripening rice,

On the right below me

The waters of the Angry Sea.

Station 35 - Kanazawa

Across the mountains of Unohana-yama and the valleys of Kurikara- dani, I entered the city of Kanazawa on July the fifteenth, where I met a merchant from Osaka named Kasho who invited me to stay at his inn.

There was in this city a man named Issho whose unusual love of poetry had gained him a lasting reputation among the verse writers of the day. I was told, however, that he had died unexpectedly in the winter of the past year. I attended the memorial service held for him by his brother.

Move, if you can hear,

Silent mound of my friend,

My wails and the answering

Roar of autumn wind.

A visit to a certain hermitage:

On a cool autumn day,

Let us peel with our hands

Cucumbers and mad-apples

For our simple dinner.

Station 36 - Komatsu

A poem composed on the road:

Red, red is the sun,

Heartlessly indifferent to time,

The wind knows, however,

The promise of early chill.

At the place called Dwarf Pine:

Dwarfed pine is indeed

A gentle name, and gently

The wind brushes through

Bush-clovers and pampas.

I went to the Tada Shrine located in the vicinity, where I saw Lord Sanemori's helmet and a piece of brocaded cloth that he had worn under his armor. According to the legends, these were given him by Lord Yoshitomo while he was still in the service of the Minamotos.* The helmet was certainly an extraordinary one, with an arabesque of gold crysanthemums covering the visor and the ear plate, a fiery dragon resting proudly on the crest, and two curved horns pointing to the sky. The chronicle of the shrine gave a vivid account of how, upon the heroic death of Lord Sanemori,* Kiso no Yoshinaka had sent his important retainer Higuchi no Jiro to the shrine to dedicate the helmet with a letter of prayer.

I am awe-struck

To hear a cricket singing

Underneath the dark cavity

Of an old helmet.*

Station 37 - Natadera

On my way to Yamanaka hot spring, the white peak of Mount Shirane overlooked me all the time from behind. At last I came to the spot where there was a temple hard by a mountain on the left. According to the legend, this temple was built to enshrine Kannon, the great goddess of mercy, by the Emperor Kazan, when he had finished his round of the so-called Thirty- three Sacred Temples, and its name Nata was compounded of Nachi and Tanigumi, the first and last of these temples respectively. There were beautiful rocks and old pines in the garden, and the goddess was placed in a thatched house built on a rock. Indeed, the entire place was filled with strange sights.

Whiter far

Than the white rocks

Of the Rock Temple

The autumn wind blows.

I enjoyed a bath in the hot spring whose marvelous properties had a reputation of being second to none, except the hot spring of Ariake.

Bathed in such comfort

In the balmy spring of Yamanaka,

I can do without plucking

Life-preserving chrysanthemums

The host of the inn was a young man named Kumenosuke. His father was a poet and there was an interesting story about him: one day, when Teishitsu (later a famous poet in Kyoto but a young man then) came to this place, he met this man and suffered a terrible humiliation because of his ignorance of poetry, and so upon his return to Kyoto, he became a student of Teitoku and never abandoned his studies in poetry till he had established himself as an independent poet. It was generally believed that Teishitsu gave instruction in poetry free of charge to anyone from this village throughout his life. It must be admitted, however, that this is already a story of long ago.

My companion, Sora, was seized by an incurable pain in his stomach. So he decided to hurry, all by himself, to his relatives in the village of Nagashima in the province of Ise. As he said good-bye he wrote:

No matter where I fall

On the road

Fall will I to be buried

Among the flowering bush-clovers.

I felt deeply in my heart both the sorrow of one that goes and the grief of one that remains, just as a solitary bird separated from his flock in dark clouds, and wrote in answer:

From this day forth, alas,

The dew-drops shall wash away

The letters on my hat

Saying 'A party of two.'

Station 38 - Daishoji

I stopped overnight at the Zenshoji Temple near the castle of Daishoji, still in the province of Kaga. Sora, too, had stayed here the night before and left behind the following poem:

All night long

I listened to the autumn wind

Howling on the hill

At the back of the temple.

Sora and I were separated by the distance of a single night, but it was just the same as being separated by a thousand miles. I, too, went to bed amidst the howling of the autumn wind and woke up early the next morning amid the chanting of the priests, which was soon followed by the noise of the gong calling us to breakfast. As I was anxious to cross over to the province of Echizen in the course of the day, I left the temple without lingering, but when I reached the foot of the long approach to the temple, a young priest came running down the steps with a brush and ink and asked me to leave a poem behind. As I happened to notice some leaves of willow scattered in the garden, I wrote impromptu,

I hope to have gathered

To repay your kindness

The willow leaves

Scattered in the garden.

and left the temple without even taking time to refasten my straw sandals.

Hiring a boat at the port of Yoshizaki on the border of the province of Echizen, I went to see the famous pine of Shiogoshi. The entire beauty of this place, I thought, was best expressed in the following poem by Saigyo.

Inviting the wind to carry

Salt waves of the sea,

The pine tree of Shiogoshi

Trickles all night long

Shiny drops of moonlight.

Should anyone ever dare to write another poem on this pine tree it would be like trying to add a sixth finger to his hand.

Station 39 - Maruoka

I went to the Tenryuji Temple in the town of Matsuoka, for the head priest of the temple was an old friend of mine. A poet named Hokushi had accompanied me here from Kanazawa, though he had never dreamed of coming this far when he had taken to the road. Now at last he made up his mind to go home, having composed a number of beautiful poems on the views we had enjoyed together. As I said good-bye to him, I wrote:

Farewell, my old fan.

Having scribbled on it,

What could I do but tear it

At the end of summer?

Making a detour of about a mile and a half from the town of Matsuoka, I went to the Eiheiji Temple. I thought it was nothing short of a miracle that the priest Dogen had chosen such a secluded place for the site of the temple.

Station 40 - Fukui

The distance to the city of Fukui was only three miles. Leaving the temple after supper, however, I had to walk along the darkening road with uncertain steps. There was in this city a poet named Tosai whom I had seen in Edo some ten years before. Not knowing whether he was already dead or still keeping his bare skin and bones, I went to see him, directed by a man whom I happened to meet on the road. When I came upon a humble cottage in a back street, separated from other houses by a screen of moon-flowers and creeping gourds and a thicket of cockscomb and goosefoot left to grow in front, I knew it was my friend's house. As I knocked at the door, a sad looking woman peeped out and asked me whether I was a priest and where I had come from. She then told me that the master of the house had gone to a certain place in town, and that I had better see him there if I wanted to talk to him. By the look of this woman, I took her to be my friend's wife, and I felt not a little tickled, remembering a similar house and a similar story in an old book of tales. Finding my friend at last, I spent two nights with him. I left his house, however, on the third day, for I wanted to see the full moon of autumn at the port town of Tsuruga. Tosai decided to accompany me, and walked into the road in high spirits, with the tails of his kimono tucked up in a somewhat strange way.

Station 41 - Tsuruga

The white peak of Mount Shirane went out of sight at long last and the imposing figure of Mount Hina came in its stead. I crossed the bridge of Asamuzu and saw the famous reeds of Tamae, already coming into flower.* Through the barrier-gate of Uguisu and the pass of Yuno, I came to the castle of Hiuchi, and hearing the cries of the early geese at the hill named Homecoming, I entered the port of Tsuruga on the night of the fourteenth. The sky was clear and the moon was unusually bright. I said to the host of my inn, 'I hope it will be like this again tomorrow when the full moon rises.' He answered, however, 'The weather of these northern districts is so changeable that, even with my experience, it is impossible to foretell the sky of tomorrow.' After a pleasant conversation with him over a bottle of wine, we went to the Myojin Shrine of Kei, built to honor the soul of the Emperor Chuai.* The air of the shrine was hushed in the silence of the night, and the moon through the dark needles of the pine shone brilliantly upon the white sand in front of the altar, so the ground seemed to have been covered with early frost. The host told me it was the Bishop of Yugyo II who had first cut the grass, brought the sand and stones, and then dried the marshes around the shrine, the ritual being known as the sand-carrying ceremony of Yugyo.

The moon was bright

And divinely pure

Upon the sand brought in

By the Bishop Yugyo.

It rained on the night of the fifteenth, just as the host of my inn had predicted.

The changeable sky

Of the northern districts

Prevented me from seeing

The full moon of autumn.

Station 42 - Ironohama

It was fine again on the sixteenth. I went to the Colored Beach to pick up some pink shells. I sailed the distance of seven miles in a boat and arrived at the beach in no time, aided by a favorable wind. A man by the name of Tenya accompanied me, with servants, food, drinks and everything else he could think of that we might need for our excursion. The beach was dotted with a number of fisherman's cottages and a tiny temple. As I sat in the temple drinking warm tea and sake, I was overwhelmed by the lonliness of the evending scene.

Lonlier I thought

Than the Suma beach -

The closing of autumn

On the sea before me.

Mingled with tiny shells

I saw scattered petals

Of bush-clovers

Rolling with the waves.

I asked Tosai to make a summary of the day's happenings and leave it at the temple as a souvenir.

Station 43 - Ogaki

As I returned to Tsuruga, Rotsu met me and accompanied me to the province of Mino. When we entered the city of Ogaki on horseback, Sora joined us again, having arrived from the province of Ise; Etsujin, too, came hurrying on horseback, and we all went to the house of Joko, where I enjoyed reunion with Zensen, Keiko, and his sons and many other old friends of mine who came to see me by day or by night. Everybody was overjoyed to see me as if I had returned unexpectedly from the dead. On September the sixth, however, I left for the Ise Shrine, though the fatigue of the long journey was still with me, for I wanted to see a dedication of a new shrine there. As I stepped into the boat, I wrote:

As firmly cemented clam shells

Fall apart in autumn,

So I must take to the road again,

Farewell, my friends.

Station 44 - Postscript

In this little book of travel is included everything under the sky - not only that which is hoary and dry but also that which is young and colorful, not only that which is strong and imposing but also that which is feeble and ephemeral. As we turn every corner of the Narrow Road to the Deep North, we sometimes stand up unawares to applaud and we sometimes fall flat to resist the agonizing pains we feel in the depths of our hearts.* There are also times when we feel like taking to the road ourselves, seizing the raincoat lying nearby, or times when we feel like sitting down till our legs take root, enjoying the scene we picture before our eyes. Such is the beauty of this little book that it can be compared to the pearls which are said to be made by the weeping mermaids in the far off sea. What a travel it is indeed that is recorded in this book, and what a man he is who experienced it. The only thing to be regretted is that the author of this book, great man as he is, has in recent years grown old and infirm with hoary frost upon his eyebrows.

Early summer of the seventh year of Genroku (1694), Soryu.

-----------------------------------------------------

Oku no hosomichi Bibliograpy

http://etext.virginia.edu/japanese/basho/index.html (Japanese text)

http://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/search.php?cndbn=%82%a8%82%ad%82%cc%82%d9%82%bb%93%b9 (facsimile Japanese texts)

Matsuo Basho's Narrow Road to the Deep North tr. by Nobuyuki Yuasa (Penguin Books, original edition 1966; reprint 1996)

A Haiku Journey, Basho's The Narrow Road to a Far Province, translated by Dorothy Britton (Kodansha; original edition: 1974, reprinted 2002)

http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~kohl/basho/1-prologue/trans-britton.html

Back Roads to Far Towns by Cid Corman & Kamaike Susume, Grossman Publishers, 1968.

http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~kohl/basho/1-prologue/trans-corman.html

The Narrow Road to the Interior trans. by Helen Craig McCullough in: Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology (Stanford University Press, 1990)

http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~kohl/basho/1-prologue/trans-mccullough.html

Japanese Poetic Diaries by Earl Miner, University of California, 1976.

http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~kohl/basho/1-prologue/trans-miner.html

The Narrow Road to the Deep North tr. by Tim Chilcott

The Narrow Road to Oku, Translated by Donald Keene (Kodansha International 1996)

Basho's Narrow Road, translated from the Japanese with annotations by Hiroaki Sato (Stone Bridge Press, 1996

Narrow Road to the Interior and Other Writings, translated by Sam Hamill (Shambala, 2000)

Bashô: Journaux de voyage, tr. René Sieffert (Pof, 1988)

Bashô's Journey, tr. David Landis Barnhill (State University of New York Press, 2005)

Oku no hosomichi - poems tr. by Haider A. Khan & Tadashi Kondo

http://www.e.u-tokyo.ac.jp/cirje/research/papers/khan/poems/okunohosomichi.pdf

Haider A. Khan is currently a professor of economics at the Graduate School of International Studies, University of Denver and at the Graduate School of Economics, University of Tokyo. Prof. Khan is also an award-winning poet , translator and literary critic. He has written on Octavio Paz, Guillaume Apollinaire, James Joyce and the Japanese Haiku master Basho, among others. His own poetry deals with the complex psychological landscape of the exiled and the displaced, among other themes.

http://www.e.u-tokyo.ac.jp/cirje/research/papers/khan/khan.html

Translations of Basho's Narrow Road, a comparison

*

Page providing scans of many of Buson's images in his Illustrated Scroll of Oku no hosomichi (Oku no hosomichi ga maki): http://www.bashouan.com/psBashouPt_ezu.htm

Support material for Matsuo Bashô's Narrow Road to the Deep North

Marguerite Yourcenar sur La Sente Etroite du Bout-du-Monde de Bashô Matsuo

http://www.motsuji.or.jp/gikeido/english/basho/index.html

引用文献

|