ボブ・ディラン : Bob Dylan (音楽家・作詞家・歌手)スウェーデン・アカデミーは13日、2016年のノーベル文学賞を米国のシンガー・ソングライター、ボブ・ディラン氏(75)に授与すると発表した。歌手の同賞受賞は初めて。スウェーデン・アカデミーは授賞理由を「偉大なアメリカの歌の伝統のなかで、新たな詩的表現を創造した」と説明した。音楽表現が文学賞の対象とされた点で画期的といえる• BobDylan.com - 公式サイト(英語) The Story Of The Cutting Edge ミックスリスト - The Story Of The Cutting (1 ~50本) ★ Blowin'The Wind ボブ・ディラン 風に吹かれてミックスリスト - Bob Dylan-Blowin' in the wind-lyrics風に吹かれて Blowin' In The Wind : Bob Dylan (ボブ・ディランを象徴する曲で、プロテストソングの名作として今でも歌われている。1963年にリリースされ、アルバム "Free Wheelin' に収録された) ・How many roads must a man walk down Before you call him a man? Yes, 'n' how many seas must a white dove sail Before she sleeps in the sand? Yes, 'n' how many times must the cannon balls fly Before they're forever banned? The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind, The answer is blowin' in the wind. ・How many years can a mountain exist Before it's washed to the sea? Yes, 'n' how many years can some people exist Before they're allowed to be free? Yes, 'n' how many times can a man turn his head, Pretending he just doesn't see? The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind, The answer is blowin' in the wind. ・How many times must a man look up Before he can see the sky? Yes, 'n' how many ears must one man have Before he can hear people cry? Yes, 'n' how many deaths will it take till he knows That too many people have died? The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind, The answer is blowin' in the wind. ・どれほどの道を歩かねばならぬのか 男と呼ばれるために どれほど鳩は飛び続けねばならぬのか 砂の上で安らげるために どれほどの弾がうたれねばならぬのか 殺戮をやめさせるために その答えは 風に吹かれて 誰にもつかめない ・どれほど悠久の世紀が流れるのか 山が海となるには どれほど人は生きねばならぬのか ほんとに自由になれるために どれほど首をかしげねばならぬのか 何もみてないというために その答えは 風に吹かれて 誰にもつかめない ・どれほど人は見上げねばならぬのか ほんとの空をみるために どれほど多くの耳を持たねばならぬのか 他人の叫びを聞けるために どれほど多くの人が死なねばならぬのか 死が無益だと知るために その答えは 風に吹かれて 誰にもつかめない ★ Bob Dylan The Times They Are A Changin' 時代は動く (1964 )ミックスリスト - Bob Dylan The Times They Are時代は動く The Times They Are A-Changin' (1964年にリリースされたこの曲も、プロテストソングとして、1960年代の若者に熱狂的に支持された) ・Come gather 'round people Wherever you roam And admit that the waters Around you have grown And accept it that soon You'll be drenched to the bone. If your time to you Is worth savin' Then you better start swimmin' Or you'll sink like a stone For the times they are a-changin'. ・Come writers and critics Who prophesize with your pen And keep your eyes wide The chance won't come again And don't speak too soon For the wheel's still in spin And there's no tellin' who That it's namin'. For the loser now Will be later to win For the times they are a-changin'. ・Come senators, congressmen Please heed the call Don't stand in the doorway Don't block up the hall For he that gets hurt Will be he who has stalled There's a battle outside And it is ragin'. It'll soon shake your windows And rattle your walls For the times they are a-changin'. ・Come mothers and fathers Throughout the land And don't criticize What you can't understand Your sons and your daughters Are beyond your command Your old road is Rapidly agin'. Please get out of the new one If you can't lend your hand For the times they are a-changin'. ・The line it is drawn The curse it is cast The slow one now Will later be fast As the present now Will later be past The order is Rapidly fadin'. And the first one now Will later be last For the times they are a-changin'. ・仲間を求めるがよい どこにいようとも 君の周りでは 流れが渦巻いてる だから気をつけろ でないと溺れるぞ もし君に 未来があるなら ちゃんと泳ぐんだ 沈んでしまわないように 時代は動いていくのだから ・作家や批評家たち 予言者を自認するものよ 目を見開きたまえ 時代をよく見るんだ 早急な物言いはするな 歯車が回らないうちに 誰が勝者で誰が 敗者かというな 今負けたものが 明日には勝つこともある 時代は動いていくのだから ・上院議員や下院議員 謙虚であれ 威張り散らすのが 能ではない 世の中は色々で 人々もさまざまだ 議会の外では 嵐が渦巻き 君たちの足元を 掬わないとも限らない 時代は動いていくのだから ・お母さんやお父さん 国中の大人たち 嘆いてはいけない 自分の理解を超えたことを あなたたちの子供たちは あなたたちには理解できない あなたたちの生き方は 通じないのだ 余計な世話は無用だ できないことはできないのだ 時代は動いていくのだから ・ラインが引かれると 呪いが放たれる 足の遅いやつだって 早くなることもある 今新しいことも 明日には古くなる 秩序だって 混沌に変わる 正義だって 悪徳になる 時代は動いていくのだから ★ ミスター・タンブリン・マン(Mr. Tambourine Man)ミックスリスト - Top 10 Bob Dylan Songsミスター・タンバリンマン Mr. Tambourine Man : Bob Dylan ・Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, I'm not sleepy and there is no place I'm going to. Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, In the jingle jangle morning I'll come followin' you. ・Though I know that evenin's empire has returned into sand, Vanished from my hand, Left me blindly here to stand but still not sleeping. My weariness amazes me, I'm branded on my feet, I have no one to meet And the ancient empty street's too dead for dreaming. ・Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, I'm not sleepy and there is no place I'm going to. Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, In the jingle jangle morning I'll come followin' you. ・Take me on a trip upon your magic swirlin' ship, My senses have been stripped, my hands can't feel to grip, My toes too numb to step, wait only for my boot heels To be wanderin'. I'm ready to go anywhere, I'm ready for to fade Into my own parade, cast your dancing spell my way, I promise to go under it. ・Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, I'm not sleepy and there is no place I'm going to. Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, In the jingle jangle morning I'll come followin' you. ・Though you might hear laughin', spinnin', swingin' madly across the sun, It's not aimed at anyone, it's just escapin' on the run And but for the sky there are no fences facin'. And if you hear vague traces of skippin' reels of rhyme To your tambourine in time, it's just a ragged clown behind, I wouldn't pay it any mind, it's just a shadow you're Seein' that he's chasing. ・Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, I'm not sleepy and there is no place I'm going to. Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, In the jingle jangle morning I'll come followin' you. ・Then take me disappearin' through the smoke rings of my mind, Down the foggy ruins of time, far past the frozen leaves, The haunted, frightened trees, out to the windy beach, Far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow. Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free, Silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands, With all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves, Let me forget about today until tomorrow. ・Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, I'm not sleepy and there is no place I'm going to. Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me, In the jingle jangle morning I'll come followin' you. ・ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ ぼくは眠くもないし でかけるあてもない ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ 歌のリズムに乗って ついていくから ・わかったんだよ ぼくは 夕闇の心地よさはぼくに 縁がないんだって それでぼくは立ち尽くしたまま 眠ることもなく 会う人もなく 夢にみるような世界も持ってないんだって ・ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ ぼくは眠くもないし でかけるあてもない ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ 歌のリズムに乗って ついていくから ・君のめくるめく船にぼくを乗せておくれよ ぼくはすっかり力がなえて 手はつかむことができないし つま先はかじかんじまって ブーツが勝手にぼくを 運ぶ始末さ この際どこへでも行くよ どうでもいいんだ だからぼくの行く道を示してくれよ そのとおりにいくから ・ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ ぼくは眠くもないし でかけるあてもない ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ 歌のリズムに乗って ついていくから ・もし君が笑い声や金切り声を聞いたとしても それにはたいした意味はないんだ とどろいてるだけさ 太陽にかんかんと照らされながらね もし君が調子のよいリズムを聞いたとしても それはお調子者がふざけているだけなんだ 気にすることはないさ つまらないことさ ほっといていいよ ・ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ ぼくは眠くもないし でかけるあてもない ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ 歌のリズムに乗って ついていくから ・ぼくはなんだか心が煙の輪のようになって たゆたってるように感じるよ 木々の葉っぱの あいだをただよいなふがら なぎさのほうへとね そこはこの世の馬鹿騒ぎとは無縁だ 片手を振りながらダンスするのに相応しい場所だ 海を背景にして 砂に絡まれながら 思い出も時の運も波にさらわれていく 明日になるまで今日のことは忘れて ・ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ ぼくは眠くもないし でかけるあてもない ヘイ ミスター・タンバリンマン 歌っておくれよ 歌のリズムに乗って ついていくから ★ 「ライク・ア・ローリング・ストーン」(Like a Rolling Stone)ミックスリスト - Top 10 Bob Dylan Songsライク・ア・ローリング・ストーン Like A Rolling Stone : Bob Dylan (1965年にリリースされた。それまでのフォーク調にロックを取り入れたフォーク・ロックとよばれるジャンルの曲で、ボブ・ディランの代表作のひとつとなった) ・Once upon a time you dressed so fine You threw the bums a dime in your prime, didn't you? People'd call, say, "Beware doll, you're bound to fall" You thought they were all kiddin' you You used to laugh about Everybody that was hangin' out Now you don't talk so loud Now you don't seem so proud About having to be scrounging for your next meal. ・How does it feel How does it feel To be without a home Like a complete unknown Like a rolling stone? ・You've gone to the finest school all right, Miss Lonely But you know you only used to get juiced in it And nobody has ever taught you how to live on the street And now you find out you're gonna have to get used to it You said you'd never compromise With the mystery tramp, but now you realize He's not selling any alibis As you stare into the vacuum of his eyes And ask him do you want to make a deal? ・How does it feel How does it feel To be on your own With no direction home Like a complete unknown Like a rolling stone? ・You never turned around to see the frowns on the jugglers and the clowns When they all come down and did tricks for you You never understood that it ain't no good You shouldn't let other people get your kicks for you You used to ride on the chrome horse with your diplomat Who carried on his shoulder a Siamese cat Ain't it hard when you discover that He really wasn't where it's at After he took from you everything he could steal. ・How does it feel How does it feel To be on your own With no direction home Like a complete unknown Like a rolling stone? ・Princess on the steeple and all the pretty people They're drinkin', thinkin' that they got it made Exchanging all kinds of precious gifts and things But you'd better lift your diamond ring, you'd better pawn it babe You used to be so amused At Napoleon in rags and the language that he used Go to him now, he calls you, you can't refuse When you got nothing, you got nothing to lose You're invisible now, you got no secrets to conceal. ・How does it feel How does it feel To be on your own With no direction home Like a complete unknown Like a rolling stone? ・きれいに着飾ってたときもあった 宿無しに銭をくれてやったこともあった そうだね みんなはいった お嬢さんそんなことするもんじゃない だけど君は相手にしなかったね 君は高笑いをしながら 周りのものを笑い飛ばした だけど今は違う 君は誇りを忘れたように 食べ物の算段をしながら暮らしてる ・どんな気持ちだい どんな気持ちだい 宿無しの境遇は 誰にも相手にされず ライク・ア・ローリング・ストーン ・ちゃんとしたハイスクールを出たんだ そうだね でもそこでは何も学ぶことがなかった 誰も路上生活のこつなど教えてくれなかった いまじゃ自分でそのこつをつかまなけりゃ 君は言ったね 変な男なんかは 絶対相手にしないって だけど 男は君に近づいてくる 君は男のうつろな目を覗き込みながら あたしとやりたいのって聞くはめになるんだ ・どんな感じだい どんな感じだい 一人で生きるって 帰る家もなく 誰にも相手にされず ライク・ア・ローリング・ストーン ・周りを見渡してみろよ 男たちはみな不機嫌な顔だ あいつらが君のところに近づいてくるとき そんなときにあいつらを足蹴にしてはいけない そんなことをしては生きてはいけない 君はこぎれいな男と馬に乗ったこともあった その男は背中にシャムネコをかついでいた 君にとってはつらいかもしれない そんな男とはもう縁がないのだから ・どんな感じだい どんな感じだい 一人で生きるって 帰る家もなく 誰にも相手にされず ライク・ア・ローリング・ストーン ・塔の上のプリンセスも世間の人々も みなそれぞれ満ち足りた暮らしをしてる 互いにすてきな贈り物を贈りあったり でも君にはほかに何もないから 指輪を質屋に入れろよ 君は仲良くしてたじゃないか ぼろをまとったナポレオンというやつと あいつのところへ行けよ 呼んでるぞ 君は何も持ってないから 失うものもない 君は誰にも見えない 隠すような秘密もない ・どんな感じだい どんな感じだい 一人で生きるって 帰る家もなく 誰にも相手にされず ライク・ア・ローリング・ストー ★ 「天国への扉」 ("Knockin' on Heaven's Door") Bob Dylanミックスリスト - Bob Dylan- Knockin' on Heaven's天国への扉 Knockin' On Heaven's Door : Bob Dylanr (1973年の映画 "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid" のために、ボブ・ディランの作った曲。歌の内容は死に行く保安官ギャレットの最後の言葉をテーマにしたものだ。バッジもガンも、保安官のシンボル) しかし、映画を離れ、ひとりの少年の死を歌ったものだとも再解釈できる。そのため、映画の主題歌としてではなく、死を歌った普遍的な曲として、世界中で歌われるようになった。 ・Mama, take this badge off of me I can't use it anymore. It's gettin' dark, too dark for me to see I feel like I'm knockin' on heaven's door. ・Knock, knock, knockin' on heaven's door Knock, knock, knockin' on heaven's door Knock, knock, knockin' on heaven's door Knock, knock, knockin' on heaven's door ・Mama, put my guns in the ground I can't shoot them anymore. That long black cloud is comin' down I feel like I'm knockin' on heaven's door. ・Knock, knock, knockin' on heaven's door Knock, knock, knockin' on heaven's door Knock, knock, knockin' on heaven's door Knock, knock, knockin' on heaven's door ・ママ このバッジをはずしてよ もう役に立たないから 目の前が暗くて 何も見えない 天国の扉を叩いてる気分 ・ノック ノック 天国への扉を ノック ノック 天国への扉を ノック ノック 天国への扉を ノック ノック 天国への扉を ・ママ このガンを埋めといて もう撃つことはないから 真っ黒な雲が垂れ下がってきて 天国の扉を叩いてる気分 ・ノック ノック 天国への扉を ノック ノック 天国への扉を ノック ノック 天国への扉を ノック ノック 天国への扉を ボブ・ディラン Bob Dylanの歌詞風に吹かれて Blowin' In The Wind:ボブ・ディラン |

ボブ・ディラン : Bob Dylanフリー百科事典

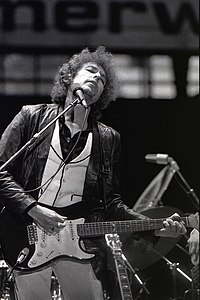

「Azkena Rock Festival」に出演するディラン(2010年6月26日)

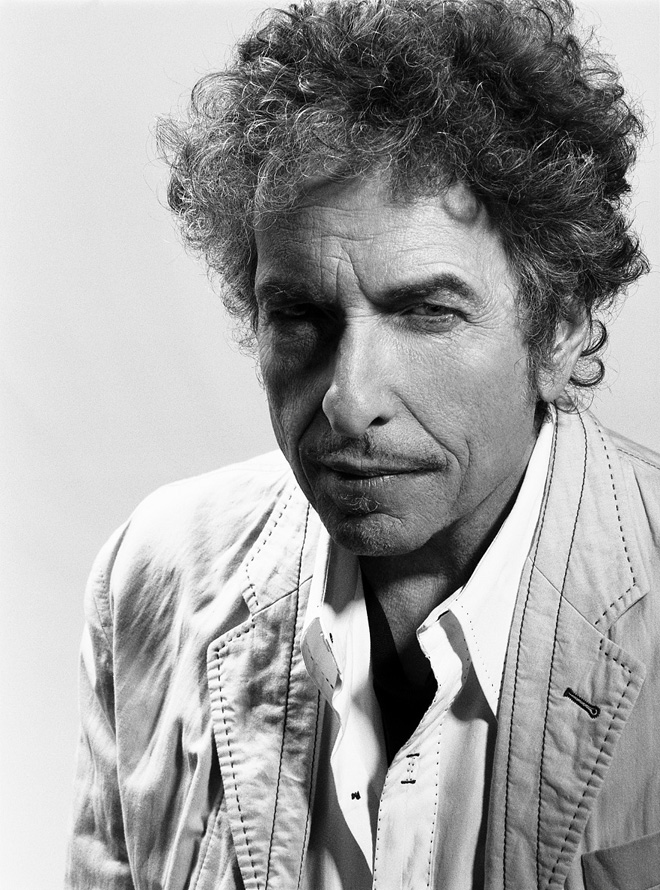

ボブ・ディラン(英語: Bob Dylan、1941年5月24日 - )は、アメリカのミュージシャン。出生名はロバート・アレン・ツィンマーマン(Robert Allen Zimmerman)だが[1][2][3]、後に自ら法律上の本名もボブ・ディランに改名している[4][5]。 「風に吹かれて」、「時代は変る」、「ミスター・タンブリン・マン」、「ライク・ア・ローリング・ストーン」、「見張塔からずっと」、「天国への扉」他多数の楽曲により、1962年のレコードデビュー以来半世紀以上にわたり多大なる影響を人々に与えてきた。現在でも、「ネヴァー・エンディング・ツアー」と呼ばれる年間100公演ほどのライブ活動を中心にして活躍している。 グラミー賞やアカデミー賞をはじめ数々の賞を受賞し、ロックの殿堂入りも果たしている。また長年の活動により、2012年に大統領自由勲章を受章している。そのほか、2008年には「卓越した詩の力による作詞がポピュラー・ミュージックとアメリカ文化に大きな影響与えた」としてピューリッツァー賞特別賞を、2016年に歌手としては初めてのノーベル文学賞を受賞した[6]。 「Q誌の選ぶ歴史上最も偉大な100人のシンガー」において第18位[7]、「ローリング・ストーンの選ぶ歴史上最も偉大な100人のシンガー」において第7位、「ローリング・ストーンの選ぶ歴史上最も偉大な100組のアーティスト」において第2位、「ローリング・ストーンの選ぶ歴史上最も偉大な100人のソングライター」において第1位を獲得している。 人物しばしば「世代の代弁者」と崇められ、メッセージソングやプロテストソングの旗手と評される(たとえば、ライオネル・リッチーは「時事的な歌に運命を開いた人」とボブを紹介している)。しかしながら、このようなことを本人は迷惑に感じており、同世代については「ほとんど共通するものも無いし、知らない」と述べ、自分の詩が勝手に解釈され、運動の象徴として扱われることに辟易していると明かす。自身の関心事は「平凡な家庭を築く」「自分の子供の少年野球と誕生日パーティー」と述べている[8]。 英セント・アンドルーズ大学や、米プリンストン大学は、彼に名誉博士号を与えている。「現行の音楽をすべて忘れて、ジョン・キーツやメルヴィルを読んだり、ウディ・ガスリー、ロバート・ジョンソンを聴くべし」と後進のアーティストに提言している。 2012年10月発売の米誌ローリング・ストーン(フランス語版)のインタビューで米国の人種間関係について問われた際に、「奴隷主や(クー・クラックス・)クランの血が混じっている人がいれば黒人はそれを感じ取る。そういうことは今日にも残っている。ユダヤ人ならナチスの血を感じ取り、セルビア人ならクロアチア人の血を感じるように」などと応じ、クロアチア人に対する憎悪を煽情する発言として在仏クロアチア人協議会から告訴された。2013年11月中旬、これを受けたフランス司法当局により侮辱行為と憎悪扇動の罪で刑事訴追されたが[9][10][11]、2014年4月15日にパリの裁判所により訴えは棄却された[12]。 経歴生い立ち1941年5月24日、ミネソタ州ダルースに生まれる[13][14][15][注 1]。ヘブライ語の名はシャブタイ・ツィメルマン(シャプサイ・ジスル)(イディッシュ語: שַׁבְּתַאי זיסל בֶּן אַבְרָהָם צימערמאַן Šabsay Zisl ben Avrohom Tsimerman)。ジスルはイスロエルの愛称。祖父母はロシアのオデッサ(現ウクライナ)やリトアニアからの移民であり、父エイブラハム・ジマーマンと母ビアトリス・ストーン(愛称ビーティー)は小規模だが絆の固いミネソタのアシュケナジム・ユダヤ人の一員だった[16][17]。1946年、弟デイヴィッド誕生[18]。1947年頃、一家はヒビングに転居する[19][20]。 幼少時より家にあったピアノを独習[21][22]。「ラジオを頻繁に聴いていた。レコード店に入り浸り、ギターをかき鳴らし、ピアノを弾いて、自分の周りにはない別の世界からの歌を覚え」て育つ[23]。初めてのアイドルはハンク・ウィリアムズ[24][25][26]。ハイスクール時代はロカビリーの全盛期で、ディランもまたエルヴィス・プレスリーらにあこがれバンドを組んで演奏活動を始める[27][28][29]。ハイスクールの卒業アルバムには「リトル・リチャードと共演すること」が夢だと記したりもしている[30]。1959年夏、ノースダコタ州ファーゴでエルストン・ガンという名でボビー・ヴィーのバンドにピアノ弾きとして入り、彼のバックでステージを数回経験する[31][32]。 1959年9月、奨学金を得てミネソタ大学に入学するも半年後には授業に出席しなくなる[33][34]。持っていたエレキ・ギターをアコースティック・ギターに交換[35]。ミネアポリスでフォーク・シンガーとしての活動を始め[36]、この時にボブ・ディランと名乗っていた[37]。「ボブ」はロバートの愛称ボビーから、「ディラン」は詩人のディラン・トーマスから取った[38]とも、また叔父の名前であるディリオンから取ったとも述べている[注 2]。アメリカ土着のブルース、ヒルビリーへの傾倒を深めていたこのころ[39]、ウディ・ガスリーのレコードを聴き大きな衝撃を受ける[40]。 1960年代ニューヨークへの移住とレコードデビュー

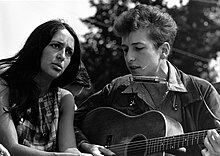

ジョーン・バエズとディラン(1963年)

1961年冬、大学を中退してニューヨークに出てきた彼は、グリニッジ・ヴィレッジ周辺のフォーク・ソングを聴かせるクラブやコーヒーハウスなどで弾き語りをしていた[41][42]が、やがてハリー・ベラフォンテのバックで初めてプロのレコーディングを経験[43]。キャロリン・ヘスターのレコーディングに参加したことや[44]、タイムズ紙で好意的に論評されたこと[45]をきっかけに[46]、コロムビア・レコードのジョン・ハモンドにその才能を見出され[47][48]、1962年3月にアルバム『ボブ・ディラン』でレコードデビューする。しかしその年の売上は5,000枚程にとどまり、コロムビアの期待していた3分の1というセールスであった[49][50]。 当初は、トラッド・フォークやブルースを中心に歌っており自作曲は少なかったが、ニューヨークで出会った人達[51]、絵画[52]、ミュージカル[53]、レコード[54]、ランボー[55]、ヴェルレーヌ、ブレイクといった象徴主義的な作風の詩人の表現技巧など、さまざまなものに創作上の影響を受け、急速に多くの新しい歌を書くようになる[56][57]。「オンリー・ア・ホーボー〜トーキン・デビル」、「ジョン・ブラウン」、「エメット・ティルのバラッド」など初期作品の一部は、トピカルソングを紹介する『ブロードサイド』誌に掲載され[58]、録音は同レーベル(後にフォークェイズ)のオムニバスに収録、ブラインド・ボーイ・グラント(Blind Boy Grunt)なる変名でクレジットされている[59][60]。 アルバート・グロスマンがマネージメントに乗り出す[61]と、幅広い活動が可能になり、ディランの楽曲を他のアーティストに提供することが考え出される[62]。しかし一方でグロスマンとハモンドが契約をめぐって対立[63]。2枚目のアルバムのレコーディング途中で、プロデューサーはトム・ウィルソンに交代する。1962年12月、ロックンロールそのもののシングル「ゴチャマゼの混乱」を発表しているが、あまりにイメージが違い過ぎたため早々に回収された[注 3]。 時代の代弁者とそれからの脱却1962年12月から1963年1月、初めてイギリスを訪れ、BBCのテレビドラマ「マッドハウス・オンキャッスル・ストリート (Madhouse on Castle Street)」に出演し[64]、ロンドンのクラブで演奏[65]。4月12日、タウンホールでソロ・コンサート[66]。5月12日、初の全米中継であるテレビ番組『エド・サリヴァン・ショー』に出演が決まるが、リハーサル後、極右政治団体のジョン・バーチ・ソサエティを揶揄した曲「ジョン・バーチ・ソサエティ・ブルース」を省くよう指示されると、検閲的行為に怒ってスタジオを出てしまった[67]。同月、モンタレー・フォーク・フェスティバルに出演。タイム誌は「新たなるヒーロー」と紹介した[68]。共演したジョーン・バエズは、以後積極的にディランの楽曲を歌い行動を共にすることが多くなる。 1963年5月、セカンド・アルバム『フリーホイーリン・ボブ・ディラン』リリース。6月、ミシシッピー州グリーンウッド選挙人登録集会で演奏。7月、ピーター・ポール&マリーがカバーした「風に吹かれて」がビルボード2位のヒットを記録する。同月、ニューポート・フォーク・フェスティバルに出演[注 4]。8月28日、ワシントン大行進で演奏。公民権運動が高まりを見せていたアメリカにおいてディランは次第に「フォークの貴公子」として大きな支持を受け、時代の代弁者とみなされるようになっていった。10月26日、カーネギー・ホールでソロ・コンサート[注 5]。1964年1月、アルバム『時代は変る』リリース。しかし、過激化する運動や世間が抱いている大げさな自分のイメージに違和感を持ち、次第にスタイルを変化させ、次のアルバム『アナザー・サイド・オブ・ボブ・ディラン』(1964年)では、プロテストソングと呼べる曲はなくなっている。10月31日、フィルハーモニック・ホール「ハロウィーン・コンサート」(『アット・フィルハーモニック・ホール(ブートレッグ・シリーズ第6集)』(2004年)収録)。 またこのころから、ディランの楽曲をカバーするアーティストが目立つようになってきた。中でもザ・バーズによる「ミスター・タンブリンマン」はビルボードで1位を獲得している。「悲しきベイブ ("It Ain't Me Babe") 」、「はげしい雨が降る」、「くよくよするなよ」、「イフ・ノット・フォー・ユー ("If Not For You") 」、「はじまりの日 ("Forever Young") 」などもよくカバーされている。 エレクトリックへの転換1964年頃からマリファナなどのドラッグの影響からか、コンサートやレコーディングでも常に少し酔っ払ったような状態になっていた。ビートルズやローリング・ストーンズをはじめイギリスのミュージシャンとの交流が芽生えたのもこの時期で、中期以降のビートルズがドラッグ体験をモチーフにした曲を多く残したのは、ディランと関わったのがきっかけとされている。なかでも1965年頃のジョン・レノンが熱病のごとく傾倒し、作風から精神面、スタイルに至るまでディランに触発された(例:[1]、[2])。またジョージ・ハリスンとは後に生涯にわたる友情を築くこととなる。 一方、ディラン自身もこれらブリティッシュ・インヴェイジョンに刺激を受け、1965年から1966年にかけて『ブリンギング・イット・オール・バック・ホーム』、『追憶のハイウェイ61』、『ブロンド・オン・ブロンド』とエレクトリック楽器を取り入れた作品を矢継ぎ早に発表した[注 6]。 従来のフォーク・ソング愛好者、とくに反体制志向のプロテストソングを好むファンなどはこの変化を「フォークに対する裏切り」ととらえ、賛否両論を巻き起こした。なかでも1965年のニューポート・フォーク・フェスティバルで、ディランはバック・バンドをしたがえて数曲演奏したが、トーキングブルースなどの弾き語りを要求するファンから手痛いブーイングの洗礼を受けた。そこでやむなくステージを降りた後、アコースティック・ギター一本で再登場し、過去の音楽との決別を示唆するかのごとく「イッツ・オール・オーヴァー・ナウ、ベイビー・ブルー ("It's All Over Now, Baby Blue") 」を涙ながらに歌いあげた[69]、という逸話が有名である(しかし、これはあくまでサイ&バーバラ・リバコブの伝記に記述された、ややドラマティックな脚色がもたらした風説である。ブーイングはひどい音響とあまりに短い演奏だったことに対するものであり、実際には歓声もあがっていたという。[70]また、バンドで用意した曲だけでは時間が余ったため、アコースティック・ギターで再度ステージに戻って数曲を披露したに過ぎないという証言も存在する)。 このようなトラブルにもかかわらず、これら3枚のアルバムでディランは従来以上に新しいファン層を獲得した。内省的で作家性の強い原曲を、アメリカ社会のさまざまなルーツミュージックやリズム&ブルースなどのバンドアレンジに乗せたこの時期の作品が、ロック史の大きなターニングポイントとして位置づけられている。また、この頃の歌詞はアレン・ギンズバーグらの文学者からも絶賛されるようになっており、ロックの歌詞が初めて文学的評価を獲得したものとして重要である。 中でもアル・クーパー、マイク・ブルームフィールドらの参加でバンド演奏を全面的に取り入れた『追憶のハイウェイ61』からのカット、「ライク・ア・ローリング・ストーン」が、キャッシュボックス誌ではじめて(そして唯一の)シングルチャートNo.1となった(ビルボードでは2位。1位はビートルズの「ヘルプ!」)。その他「寂しき4番街」が7位、「雨の日の女 (Single Edit.) 」がビルボード、キャッシュボックス誌で共に最高2位、[注 7]。"「アイ・ウォント・ユー」が20位、「女の如く」が33位を獲得するなど、次々チャートアクションを記録した。しかしその記録だけでなく、今日のミュージックシーンにおいていわゆる「ディランズ・チルドレン」を自認してきた大御所ミュージシャンに、さらに多くのフォロワーが枝分かれしている事実からも「シンガー・ソングライター」という系統を確立した役割は遥かに大きいといえる。 1965年から1966年にかけて、後にザ・バンドとなるバックバンド、レヴォン&ザ・ホークスをしたがえてワールドツアーをこなす。既述のように、ここでも初期の弾き語りを求めるファンやメッセージ性の強いラディカルな曲を好む観客からのブーイング、リズムを乱すようにしむける不規則な手拍子、足踏みなどの妨害行為は収まらず、それに対し挑戦的にバンド演奏を繰り広げるディランの姿は『ロイヤル・アルバート・ホール(ブートレッグ・シリーズ第4集)』(1998年)[注 8]、映画『イート・ザ・ドキュメント(Eat the Document)』などに収録されている[注 9]。『ロイヤル・アルバート・ホール』では、バンドが次曲の準備をしている最中に観客の一人が「ユダ(裏切り者)!」と叫ぶと、場内に賛同するような拍手やブーイング、更には逆にそれを諌める声などが起こった場面が収められている。その中でディランは「I don't believe you... You're a liar!」と言い放つと、怒涛の迫力で「ライク・ア・ローリング・ストーン」の演奏をはじめた。嵐のような演奏が終わると、放心状態だった会場からは惜しみない拍手が巻き起こったが、ディランはぶっきらぼうに「Thank you」と言い残し、そのままステージをあとにした。[注 10] またこの頃にはLSDも使用するようになっており、ビートルズやザ・ビーチ・ボーイズらと同様、作風にも大きな影響を受け、特にディランは声が大きく変化した。 この時期のアルバム未収録曲としては、「ビュイック6型の想い出 ("From a Buick 6") 」のハーモニカバージョン、「窓からはい出せ」のアル・クーパー、マイク・ブルームフィールドによるセッション(当初、「Positively 4th Street」と誤記されたシングル盤が出回ったため回収。再発売され、後に『バイオグラフ』(1985年)に収録された公式バージョンはザ・ホークスとの再録音)などがある。 バイク事故と隠遁こうして最初の絶頂期を迎えていた[71]1966年7月29日に、ニューヨーク州ウッドストック近郊で[72]オートバイ事故を起こす[73]。重傷が報じられ[74][注 11]、すべてのスケジュールをキャンセルして[75]隠遁。再起不能説や死亡説などの噂が流布した[注 12]。しかし当時、ドラッグ[76]とコンサートツアーに明け暮れ、「競争ばかりの社会から抜け出したかった」[77]ディランにとってはかえってよい休養となった[78][79]。事故の三週間程前、秘密裏に結婚していたサラ・ラウンズとの間に子供が生まれ、家族以外のことには興味を持てなくなっていたディラン[80]の大きな転機である[81][82]。 翌1967年からは、ウッドストックにこもってザ・ホークスのメンバーとともにレコード会社向けデモテープの制作に打ち込む。このセッション音源をもとにしたアセテート盤が配布され、マンフレッド・マンによる「マイティ・クイン ("Quinn the Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn)") 」がキャッシュ・ボックスで10位、全英シングル・チャートで1位を獲得するなど、様々なミュージシャンにカバーされて紹介された。ザ・ホークスは、ザ・バンドと名を改め、このセッションから生まれた「アイ・シャル・ビー・リリースト」、「ジス・ホイールズ・オン・ファイアー ("This Wheel's on Fire") 」等の楽曲を収録し、ディランが描いた絵をジャケットにしたアルバム『ミュージック・フロム・ビッグ・ピンク』(1968年)で単独デビューする。やがてディランとザ・バンドによる膨大な未発表のデモテープがディラン宅の地下室に眠っているという噂が口コミで広がったが、その後大きな問題が生じた。副産物として『グレート・ホワイト・ワンダー (Great White Wonder) 』などの海賊盤が出回り始め、闇の一大市場となってしまったのである。なお、このデモ音源の一部は1975年にロビー・ロバートソンの手により、新たにオーバーダブを加えた改良版として『地下室(ザ・ベースメント・テープス)』の題で公式発表された。 1967年にはベネルックス三国にて、地元のバンドによるコーラスをオーバーダビングした「出ていくのなら ("If You Gotta Go, Go Now") 」がシングルリリースされた。1991年リリースの『ブートレッグ・シリーズ1 - 3集』に収録されたバージョンとは全く違う、ハーモニカなしのバージョンであった。 1968年にディランは前作に引き続き、ナッシュビル録音による『ジョン・ウェズリー・ハーディング』で復帰するが、弾き語り中心で徐々にダウン・トゥ・アースのような傾向が見られはじめる。「見張塔からずっと」は、ジミ・ヘンドリックスがカバーしてヒットする。 1969年に映画『真夜中のカーボーイ』の主題歌の依頼があったが、レコーディングが間に合わず、ハリー・ニルソンの「うわさの男Everybody's Talkin'」に差し替えられるということがあった。その幻の主題歌「レイ、レディ、レイ ("Lay Lady Lay") 」は結局ノン・タイアップでリリースされたが、澄んだ声と奥行きのあるサウンドのこのシングルは全米8位のヒットとなった。ディランにとって、最後のトップ10シングルである。この曲が収録された『ナッシュヴィル・スカイライン』はまさにカントリーといっていいアルバムである。このアルバムでの澄んだ歌声についてディランは、煙草を止めたら声質が変わったと述べてはいるが、次アルバムに収録された「ザ・ボクサー」では、しゃがれ声と澄んだ声の多重録音一人二重唱をやっている。 1970年代隠遁後からレコード会社移籍まで1970年6月、『セルフ・ポートレイト』を発表。カントリー、MOR、インストを含む様々なジャンルの曲を無作為に並べた実験精神溢れるアルバムで、評価をとまどう声もあった[83]がセールスは好調であった。その直後、レコーディング拠点をナッシュビルからニューヨークに戻し、10月『新しい夜明け』を発表する。 その後、ディランはオリジナルアルバムの制作を中断。それ以降は「バングラデシュ・コンサート」への出演、ジョージ・ハリスン[84]、レオン・ラッセル[85][86]、ハッピー・トラウム[87][88]、アール・スクラッグス[89]、デヴィッド・ブロンバーグ、ロジャー・マッギン[90]、ダグ・サム[91]等とセッションしたこと以外は沈黙を守る。 1971年発表の『グレーテスト・ヒッツ第2集』にはディラン自身のリリース条件としてレオン・ラッセル、デラニー&ボニー&フレンズとのセッションから2曲、ハッピー・トラウムとのセッションから3曲、そして未発表初期音源としてタウンホールでのライブから「明日は遠く ("Tomorrow Is A Long Time") 」を一切の手を加えない状態で収録。ベスト盤にボーナス・トラックを加える先例となる。また、同年末には久々のプロテストソングである「ジョージ・ジャクソン」を発表。A面にはレオン・ラッセルとのセッションからのビッグ・バンド・バージョン、B面にはアコースティック・バージョンを収録。当時のアメリカの放送局では歌詞に問題がある曲の場合は、そのシングルのB面をかけてお茶を濁すのが慣例であったが、このシングルはB面の方が歌詞がより鮮明に聴こえて逆に効果大であった。 1973年、ビリー・ザ・キッドを題材にした映画『ビリー・ザ・キッド/21才の生涯』への出演をきっかけに活動を再開。挿入歌「天国への扉」はディランの曲の中でもカバーするアーティストが多い一曲となった[92]。 この頃CBSソニーから日本独自企画盤として『Mr. D's Collections #1』が特典として配布された。ソニーは以降も#2、#3、『傑作』(1978年)、『武道館』(1978年)、『Dylan Alive!』、『Bob Dylan Live 1961-2000』(2001年)、『ディランがROCK!』(2010年 / 当初は1993年に制作されたが、この時はディランの許可が下りず未発売だった)といった企画盤を企画している。なお、『The Never Ending Tour』という企画盤については、ディランの許可が下りていない。 またこの年、ディランはアサイラム・レコードへの移籍を決断。CBSコロムビアは報復手段として所有する膨大な過去の音源をリリースすることにし、まずは『セルフ・ポートレイト』のアウトテイク集である『ディラン』を発売する。ディランはアサイラムで2枚のアルバムを発表した後、コロムビアへ戻るが、その要因には過去の音源の権利関係があったためともいわれる。『ディラン』は一度CD化されたが、廃盤(アメリカのiTunes Music Storeではダウンロード可能)。アサイラムの二枚のアルバム『プラネット・ウェイヴス』(1974年)、『偉大なる復活』(1974年)も1977年にコロムビアから再発売となった。 ツアーへの復帰1974年、かつてのバック・バンドだったザ・バンドを従えてレコーディングした『プラネット・ウェイヴス』を発表。初のビルボードNo.1アルバムとなる。引き続き、ザ・バンドと共に全米ツアーを行った。彼等との共演は1968年のウディ・ガスリー追悼コンサート、1969年ワイト島音楽祭、1971年大晦日のザ・バンドコンサートのゲスト以来、5回目である(最後は1976年の『ラスト・ワルツ』だった)。しかし、今やスターダムにのしあがったザ・バンドとの力関係は対等になり、バンドサウンドとしては完璧で非の打ち所のないものながら、ディラン自身は退屈さをも漏らしていたようである。このツアーの模様はライブ盤『偉大なる復活』に収録された。 翌1975年には、『ブロンド・オン・ブロンド』のサウンドと『ナッシュヴィル・スカイライン』の透明感を併せ持つコロムビア復帰作『血の轍』を発表。内省的で沈鬱な内容にも関わらず、これもNo.1を獲得。ディランは当時、マリー・トラヴァース(ピーター・ポール&マリー)のラジオ番組で「なぜ、このような暗いアルバムが好かれているのか理由がわからない」と述べている。この作品は、当初ニューヨークで録音されてプレス盤も出回ったが、ディラン本人がリリース直前にストップをかけ、ミネアポリスで半数を取り直した。録音にはミック・ジャガーが立ち会った。ミックはオルガンも弾いたそうだが、採用されたかは不明。ニューヨーク音源からは「リリー、ローズマリーとハートのジャック ("Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts") 」だけが日の目を見ていない。

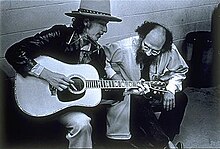

「ローリング・サンダー・レヴュー」のバックステージ。アレン・ギンズバーグと(1975年)

また1975年10月 - 12月と1976年4月 - 5月の2つの時期にかけて「ローリング・サンダー・レヴュー」と銘打ったツアーを行なった。これは事前の宣伝を行わず、抜き打ち的にアメリカ各地の都市を訪れて小規模のホールでコンサートを行なうというもので、かつてのフーテナニーのリバイバルないし、巨大産業化したロック・ミュージックに対する原点回帰の姿勢を提示した。このツアーでは、ディラン自身が監督をつとめた映画『レナルド&クララ』の撮影もあわせて行われた。このツアーの模様は『ローリング・サンダー・レヴュー(ブートレッグ・シリーズ第5集)』(2002年)、『激しい雨』(1976年)、映画『レナルド&クララ』、テレビ番組『Hard Rain』などに収録されている。このツアーメンバーを主として、ツアー開始直前に録音されたアルバム『欲望』が1976年初頭に発表され、No.1を獲得するとともに自身最大のセールスを記録した。 1978年には映画『レナルド&クララ ("Renaldo and Clara")』が公開されるが、内容が難解すぎると不評を買い、興行的には失敗。はじめは4時間弱だったが、後に2時間の短縮版が編集され再度公開。だが結局評価は変わらずじまいであった。封切りに先立ち『4 Songs From "Renald & Clara"』というプロモEPが業界内に配布された。サウンドトラック盤からの抜粋であるが、オリジナル盤は公式発表されていない。 この年は12年ぶりにワールド・ツアーを開始し、2月から3月にかけては初の来日公演を行ない、東京公演の模様が『武道館』に収録、リリースされた。1971年のレオン・ラッセル・セッション以来の女性コーラス、ホーンセクションを含むビッグバンド編成である(ディランは1987年のツアーまで女性コーラスを導入していた)。また、ツアー中には、ツアーメンバーとともに『ストリート・リーガル』を制作。日本滞在時に作曲したという「イズ・ユア・ラヴ・イン・ヴェイン ("Is Your Love in Vain?") 」も収録されており、イギリスなどでマイナー・ヒットとなった。 なお、来日記念盤として日本限定で発売された『傑作』には、アルバム未収録の「親指トムのブルースのように ("Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues", Live at Liverpool) 」、「スペイン語は愛の言葉 "Spanish Is The Loving Tongue" (Piano Solo Version) 」、「 ジョージ・ジャクソン (Big Band Version) 」、「リタ・メイ」などが収録された。後にオーストラリアとニュージーランドでCD化されたが、入手困難となっている。 クリスチャンへの洗礼ワールド・ツアー終了後、ボーン・アゲイン・クリスチャン (Born again Christianity) の洗礼を受けたことが明らかになった。 1979年発表の『スロー・トレイン・カミング』はディラン流のゴスペルで占められていた。このアルバムはマッスルショウルズの専属スタジオミュージシャン達の手により制作された[93]、ディラン初の“プロフェッショナル”なアルバムである。このアルバムは旧来のファン離れを招いた[注 13]ものの、売れに売れてグラミー賞も獲得した。本作収録曲の「ガッタ・サーヴ・サムバディ(Single Edit.)」はディラン最後のトップ40シングルである。シングルB面の "Trouble in Mind" はアルバム未収録。また、未発表の "Ain't No Man Righteous, No Not One" もレゲエ・グループのJah Mallaにカバーされるなど、この時期の曲は比較的人気が高くトリビュート・アルバムも作られている。 1980年代ゴスペルからの脱却と試行錯誤前述の『スロー・トレイン・カミング』と1980年発表の『セイヴド』、1981年発表の『ショット・オブ・ラブ』は「ゴスペル三部作」と呼ばれる。この時期のコンサートでは当初、これらの作品群からの曲しか演奏せず、批判を浴び動員も伸び悩んだ。その結果を考慮して後期のツアーでは、初期のヒット曲も織り交ぜた折衷版として妥協の姿勢も見せた。ディランはこの当時のサウンドにはかなり誇りを持っていたようで、ライブアルバムの発表を望んだが、コロムビアに拒絶された。『ショット・オブ・ラブ』のアルバム未収録曲としては "Let It Be Me" 、「デッド・マン、デッド・マン ("Dead Man, Dead Man", Live Version) 」がある。後者は1989年「ポリティカル・ワールド ("Political World") 」のカップリングで発表された後、『Live 1961-2000』に再録。 1981年にはそれまでの代表曲、未発表曲を網羅したコンピレーションアルバム『バイオグラフ』の企画が持ち上がる。発売には4年を要したため、1982年以降の曲は収録されていない。 1983年には、『スロー・トレイン・カミング』セッションに参加していたダイアー・ストレイツのマーク・ノップラーをプロデューサーに迎えて製作した『インフィデル』を発表する。この作品は前数作までのゴスペル色が薄れ、従来のファンから大いに歓迎された。しかし、ノップラーは制作途中で自身のワールドツアーに出てしまい[94]、残されたテープをディラン自身がミックスしたこのアルバムにはノップラーも含め、選曲、アレンジなどに不満の声もある。[注 14]このアルバムからのシングル「スウィートハート ("Sweetheart Like You") 」はビルボード55位だった。 この頃から時代は多重録音の手法がメインとなり、即興性を重んじるディランもまた時代性との狭間で試行錯誤を繰り返すことになる。そして、1985年、アーサー・ベイカーの手を借り、R&B、ヒップホップを彼流に取り入れた『エンパイア・バーレスク』を発表する。しかし、このアルバムは「エモーショナリー・ユアーズ ("Emotionally Yours") 」といった曲を含みながらセールス、評価ともに、同年発売のコンピレーション・アルバム『バイオグラフ』の陰に隠れて見過ごされる事態となった。この結果により、ディランはスタジオ・レコーディングに精力を傾けて商業的成功作を作ろうという気持ちを半ば諦めたともいわれる。その後の『ノックト・アウト・ローデッド』(1986年)、『ダウン・イン・ザ・グルーヴ』(1988年)は消極的なアウトテイク集にすぎないとの批判も一部から寄せられた。『ダウン・イン・ザ・グルーヴ』には、南米のいくつかの国で "Important Words" が収録されている。 他のミュージシャンとの共演・共作1985年にはUSAフォー・アフリカに参加し、「ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド」のブリッジ部分でリード・ボーカルをとった。また同年には大規模チャリティー・コンサートの「ライヴエイド」に、ローリング・ストーンズのキース・リチャーズ、ロン・ウッドとともにトリで出演。しかしながら「風に吹かれて」の途中でギターの弦が切れロン・ウッドのギターと交換せざるをえなくなるアクシデントが発生(ロン・ウッドはエア・ギターとなった)。さらに、モニタースピーカーを取り払われ、ステージ裏では他の出演者が大トリの「ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド」を練習しはじめるなど最悪のコンディションで、キースやロンともなかなかかみ合わないなど、彼自身にとってもマスコミの評価の上でも最悪の結果に終わった。 これに危機感を持ったといわれるディランは、次なるチャリティー・コンサート「ファーム・エイド」でトム・ペティ&ザ・ハートブレイカーズにバックを依頼する。このステージを縁として、翌1986年 - 1987年の共演ツアーが実現し、後に大きな話題となるトラヴェリング・ウィルベリーズ結成にもつながってゆく。ハートブレイカーズとの公式音源はビデオ "Hard To Handle" に収録。また "Bob Dylan with The Heartbreakers" 名義で「バンド・オブ・ザ・ハンド」が発表された。助力を仰いだ理由としては、1980年代はセールスも下降気味で、ディラン単独では大きなアリーナやスタジアムでの公演が難しく、サンタナやグレイトフル・デッド等とパッケージを組むしかなくなっていた当時の窮状、という側面もある。しかしながら、『リアル・ライヴ』(1984年)、『ディラン&ザ・デッド』(1989年)の2枚のライブアルバムは最低の評価を受けるなど、ディランにとってだけでなく、ディラン流のやり方[注 15]にそぐわない共演者にとっても、不本意な結果に終わることもまた多かったといわれる[要出典]。この当時、ディラン自身もやや自信喪失気味で、グレイトフル・デッドへの加入を打診したこともあったらしい[要出典]が、メンバーの反対により実現しなかった。 ディランは、トム・ペティつながりでユーリズミックスのデイヴ・ステュワートに「エモーショナリィ・ユアーズ ("Emotionally Yours") 」 "When The Night Comes Falling From The Sky" のミュージック・ビデオ制作を依頼する。ディランは数年後にジョン・メレンキャンプにも依頼しているが、ミュージシャンに映像制作を依頼する理由は謎である。 また、1987年に公開された出演映画『ハーツ・オブ・ファイヤー(Hearts Of Fire)』も不評と、この時期のディランの活動はことごとく不調であった。なお、『ハーツ・オブ・ファイヤー』のサントラにはディランの曲が3曲収録されたが、廃盤となっている。他に、ディズニーの企画盤では "This Old Man" が、ウディ・ガスリーの追悼アルバムには "Pretty Boy Floyd" が収録された。 1987年に、ダニエル・ラノワプロデュースによる『ヨシュア・トゥリー』を発表していたU2の、ワールド・ツアーのロサンゼルス公演に飛び入り参加。ボノと「アイ・シャル・ビー・リリースト」、「天国への扉」を歌った。ボノは当時、スタジオ録音に悩んでいたディランに「ラノワならディランを上手くプロデュースできるのでは」と発言している。 1988年にはロイ・オービソン、ジョージ・ハリスン、ジェフ・リン、トム・ペティと共に覆面インスタント・ユニット、トラヴェリング・ウィルベリーズを結成し、アルバム『トラヴェリング・ウィルベリーズ Vol.1』をリリース。ツアーも予定されていたが、12月6日にロイ・オービソンが心臓発作で死去したため、ツアーは幻に終わった。その後、デル・シャノンを加えた新体制で続行という噂があったが、デル・シャノンは1990年2月8日に拳銃自殺してしまう。この時期のバンドに関しては未だに詳細不明である。結局、残された4人で2枚目のアルバム『トラヴェリング・ウィルベリーズ Vol.3』(1990年)をリリースし、バンドは自然消滅した。 1989年には、ボノの進言で招聘したダニエル・ラノワの好サポートによる『オー・マーシー』を発表。ディラン自身の性来持っている南部志向を存分に引き出したが、セールスは全盛期には遠く及ばなかった。2005年に発売された自伝には当時のレコーディングのことが詳細に記述されている。収録曲「モスト・オブ・ザ・タイム "Most of the Time" 」のミュージック・ビデオには別バージョンが使われており、その音源はプロモーションCDにのみ収録された。 1990年代ネヴァー・エンディング・ツアー一連のスタジアムコンサートツアーを終えたディランは、1988年6月7日[95]より小さなホールにおいて最小限のメンバーで即興性を全面に押し出したショウをはじめることにした。このツアーは「ネヴァー・エンディング・ツアー (Never Ending Tour) 」と題され、1991年にG・E・スミスのサポートメンバー脱退を以てひとまず完結となった。これ以降のディランのツアーは、それぞれ別のタイトルがつけられているのだが、いつしかファンの間では、以降のディランのステージはおしなべて「ネヴァー・エンディング・ツアー」という名称で呼ばれるようになった。 当初はパンキッシュなアプローチも見せたが、次第にアコギとハーモニカという従来のスタイルを捨て、メロディーラインもアンサンブルもかなぐり捨て、ひたすらリードギターを弾きまくるスタイルになり、そのグルーヴ感を全面に押し出すスタイルを一部の評論家(特に小倉エージら旧来のウォッチャー)は「ボディ・ミュージック」とも形容した。ツアーメンバーには、テレビ番組「サタデー・ナイト・ライブ」も手がけたG・E・スミス(後述の30周年コンサートでもハウスバンドのギタリストとして、事実上のコンサートマスターであった)、ウィンストン・ワトソン(ジョン・ボーナムばりのパワフルなドラミングで、1990年代半ばのディランサウンドを象徴した)、チャーリー・セクストン(元ソロ歌手)などが入れ替わり立ち代わり参加している。 1990年に『アンダー・ザ・レッド・スカイ』を発表後、ディランはその後7年間自作曲のスタジオ・アルバムを作らなくなった[96]。そのことに関してインタビューで「過去にいっぱい曲を作ったので新曲を作る必要を感じない」と発言している。 その後、1997年までに発表されたものは、2枚のトラディショナル・ソングのカバー・アルバム『グッド・アズ・アイ・ビーン・トゥ・ユー』と『奇妙な世界に』、未発表曲のコンピレーション、ベスト数枚、MTVライブであった。またウィリー・ネルソンのアルバムへのゲスト参加、映画『ナチュラル・ボーン・キラーズ』への楽曲提供(ポール・アンカのカバー「ユー・ビロング・トゥ・ミー」)、マイケル・ボルトンとの共作「Time, Love And Tenderness」などもあった。 1991年2月、グラミー賞生涯功労賞(Lifetime Achievement)を受賞[97]。授賞式では湾岸戦争開始直後の好戦気分溢れる時期でありながら、「戦争の親玉」をハードロックアレンジで歌い、聴衆の度肝を抜いた。 同年には、それまでの過去の音源からの未発表曲を網羅した『ブートレッグ・シリーズ第1〜3集』を発表した。「アイ・シャル・ビー・リリースト」、「ブラインド・ウィーリー・マクテル ("Blind Willie McTell") 」、「夢のつづき ("Series Of Dreams") 」などの曲でディラン再評価の兆しになった。 1992年10月16日にはレコードデビュー30周年を祝って、マディソン・スクエア・ガーデンで記念コンサートが開催され、多くのアーティストが一堂に会してディランの代表曲を歌った。ディランは当時、過去の人扱いにも似たこの「ボブ・フェスト(ニール・ヤング命名)」にはあまり嬉しそうではなく、ステージ上でも時折ナーバスな表情を見せていた。また、出演者が勢ぞろいして歌った「マイ・バック・ページ」はCDでディランのボーカルが差し替えられていたりと、編集の形跡がみられる。 "Song to Woody" はPAの不備によりアルバム収録はならなかったが、アコギ一本で鬼気迫るリードを弾く「イッツ・オールライト・マ ("It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)") 」は満場の観客を捉えるに充分の一撃であった。 1994年、2月に8年振りに訪日コンサートを行なう。4月には奈良市東大寺境内で行なわれたユネスコ主催の音楽祭『THE GREAT MUSIC EXPERIENCE '94 〜21世紀への音楽遺産をめざして〜 AONIYOSHI』のため再訪日。東京ニューフィルハーモニック管弦楽団をバックに3曲(鐘をならせ("Ring Them Bells")、アイ・シャル・ビー・リリースド("I Shall Be Released")、激しい雨が降る("A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall"))を披露した。そのうちの1曲「はげしい雨が降る」のシンフォニックバージョンがヨーロッパ、オセアニア等でシングルCD「ディグニティ」のカップリング曲として収録されている(国によっては「悲しきベイブ(Renaldo & Clara Version)」に差し替えられている)。 夏には「ウッドストック1994 ("Woodstock '94") 」にも出演。公式アルバムには、ディランの曲からは「追憶のハイウェイ61 ("Highway 61 Revisited") 」だけが収録された。年末にはMTVの公開番組『MTVアンプラグド』に出演。1960年代の曲を中心とした選曲で、評判となる(ディランは当初古いフォーク・ソングをやることに決めていたが、ソニー側が反対した[98])。翌年『MTVアンプラグド』(1995年)のCD・ビデオがリリース。同時期、自身が設立したとされるレーベルから、ジミー・ロジャースのトリビュートアルバムを発表。 "My Blue Eyed Jane" はエミルウ・ハリス、ダニエル・ラノワとの久々の仕事であった。 7年振りのオリジナル・アルバム1997年、2月に再び訪日。5月に心臓発作で倒れ、一時は危ぶまれたものの快癒し、復帰。この時ディランは「もうすぐエルヴィスに会うのかと本気で思った。」[99][100]と発言している。その直後、三度ラノワと組み、7年ぶりにオリジナル・アルバムを発表することが明らかになり、新曲はもう聴けないと思っていたファンを狂喜させた。これに関し、自分のライブに若いファンが訪れているのを知ったディランが、彼らの為にアルバムを作ろうと思った、と述べている。このアルバム『タイム・アウト・オブ・マインド』は18年振りに全米トップ10に入り、グラミー賞年間最優秀アルバム賞を受賞した。同年には、息子であり、アメリカのロック・バンド、ザ・ウォールフラワーズ(The Wallflowers) のフロントマンでもあるジェイコブ・ディランもグラミー賞を受賞しており、親子揃っての受賞となった。 1997年9月、イタリア・ボローニャでおこなわれたカトリック教会のイベント、世界聖体大会で教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世の前で演奏。教皇は2万人の会衆に対して「風に吹かれて」の歌詞をモチーフとした説教を行った[101]。12月、ホワイトハウスにてケネディ・センター名誉賞を受賞。当時の米国大統領ビル・クリントンは、「ボブほどの衝撃を与えた同世代のクリエイティヴ・アーティストはおそらくほかにいない。」[102][103]と献辞を贈った。1999年6月から10月、ポール・サイモンとアメリカ国内ツアー。ビッグ・ネームふたりの共演に、チケットは高騰した[104]。 2000年代再評価と新作のNo.1獲得

ニューオーリンズ・ジャズ&ヘリテッジ・フェスティバルで演奏するディラン(2006年)

2000年には、映画『ワンダー・ボーイズ』に新曲「シングズ・ハヴ・チェンジド」を提供。2001年に、ゴールデングローブ賞主題歌賞[105]とアカデミー歌曲賞を受賞した[106]。 2001年2月から3月にかけて、5度目の訪日公演を行う。直後の9月11日には43枚目となるアルバム『ラヴ・アンド・セフト』を発表。奇しくもアメリカ同時多発テロの発生と同日のリリースであった。21年振りのトップ5アルバムである。 2002年ツアーより、ディランはほとんどギターを弾かなくなり、もっぱらキーボードに専念するようになった。このことに関してディランは、2004年のニューズウィーク誌のインタビューで、ギターでは彼の望んでいるサウンドを形にしきれないこと、専門のキーボードプレイヤーを頼むことも考えたが、結局自分で弾くことにした、と答えている。また、ディランはソロモン・バークが2002年7月に発表したアルバム『ドント・ギヴ・アップ・オン・ミー』に、自身の未発表曲「ステップチャイルド」を提供した[107]。 2004年3月17日にデトロイトで行われた公演で、ホワイト・ストライプスのジャック・ホワイトと共演し、ストライプスの曲をデュエット。また、この年の「Bonnaroo Festival」に出演。「入り江にそって ("Down Along The Cove") 」が、同ライブCDに収録された。 2004年10月には、ディラン自身が筆をとった自伝第1弾『ボブ・ディラン自伝(Chronicles: Volume One)』が出版された[注 16]。ショーン・ペンによる朗読CDも発売されている。また、「ディグニティ」のデモバージョン等が収録された同名の2枚組CDも仏Sony BMGよりリリースされた。 2005年7月16日に、オンライン書店アマゾン(Amazon.com)の創立10周年を記念したイベントで、ノラ・ジョーンズと「アイ・シャル・ビー・リリースト」をデュエット、この模様はインターネットでストリーミング配信された。また同年9月から10月はじめには、マーティン・スコセッシ監督によるドキュメンタリー『ノー・ディレクション・ホーム(No Direction Home: Bob Dylan)』がテレビで放映された[108][注 17]。ディラン本人の他、デイヴ・ヴァン・ロンク、スーズ・ロトロ、ジョーン・バエズ、アレン・ギンズバーグ、ピート・シーガーら関係の深い人達がインタビューに出演、サウンドトラックは未発表曲で構成され、『ノー・ディレクション・ホーム:ザ・サウンドトラック(ブートレッグ・シリーズ第7集)』としてリリースされた。この作品は、後に劇場公開されて翌年にはDVD化、2006年4月にはピーボディ賞[109]、2007年1月にはコロンビア大学デュ・ポン・アワード[110]を受賞している。 2006年3月からは、ラジオ番組『Theme Time Radio Hour』で、初めてDJを務めている(アメリカの衛星ラジオ局、MX・サテライト・ラジオの「ディープ・アルバム・ロック・チャンネル」にて放送)。この番組は、インターネットでも配信されているため、日本での聴取も可能である。5月、生まれ故郷のダルースでは、ディランゆかりの地を巡る全長1.8マイルの道路に標識が設置され、「ボブ・ディラン・ウェイ」と名付けられた。毎年5月には、誕生日を祝うイベントも開催されている。[111] 同年8月29日には、5年ぶりのアルバム『モダン・タイムズ』を発表。このアルバムは、9月16日付ビルボードアルバムチャートで『欲望』以来、30年半ぶりのNo.1を獲得[112]。しかも自身初の初登場No.1を遂げた。また、このアルバムにも収録されている「サムデイ・ベイビー("Someday Baby")」は、ビルボードで98位と23年振りのTop100シングル曲となった。米ローリング・ストーン誌や英Uncut誌は、このアルバムを2006年の年間ベスト・アルバム1位に挙げ[113][114]、2007年2月のグラミー賞では、『モダン・タイムズ』と「サムデイ・ベイビー」で2冠を獲得した。 2007年、2008年の2年間をデビュー45周年とし、「DYLAN ICON」キャンペーンを実施。全キャリアを総括するベスト盤『DYLAN』発売を皮切りに、「我が道を行く("Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I'll Go Mine)") 」のリミックスの発表、「ニューポート・フォーク・フェスティバル」完全版DVD化、『オー・マーシー』から『モダン・タイムス』のアウトテイクやライブ音源等を収録した『テル・テイル・サインズ(ブートレッグ・シリーズ第8集)』のリリース等、ディラン再評価ムーブメントを象徴する動きが見られた。 2007年10月には初の個展となる「The Drawn Blank Series」が、ドイツのケムニッツにて開催された。これは、1989年 - 1992年の間に描いたスケッチ(1994年に画集 "Drawn Blank" として発刊された)をもとに、ディラン自身が新たに手を加えて制作された絵画の展覧会である。2008年にはロンドンでも開催され、以後世界各地で展開されている。日本でも、2010年11月に東京・六本木で開催された。 2008年には「卓越した詩の力による作詞がポピュラー・ミュージックとアメリカ文化に大きな影響与えた」としてピューリッツァー賞特別賞を受賞した[115]。2009年4月、スタジオ・アルバム33作目となる『トゥゲザー・スルー・ライフ』をリリース。ビルボード200と全英アルバム・チャートの両チャートで初登場1位を記録した[116][117]。10月、売上印税を国際的な慈善機関に寄付するクリスマス・アルバム『クリスマス・イン・ザ・ハート』をリリース[118]。2010年3月には、9年振り6度目の来日公演で、Zepp OsakaとZepp Nagoya、Zepp Tokyoの3か所で行われた[119]。 レコードデビュー50周年を迎えた2012年には、アメリカ大統領のバラク・オバマより大統領自由勲章(文民に贈られる最高位の勲章)が授与された。9月には、35作目となる『テンペスト』をリリースした。 2016年10月13日、ノーベル文学賞を授与されることが発表された[6]。 影響・語録など

日本公演

ディスコグラフィ詳細は「 ボブ・ディランの作品 」を参照

受賞各賞詳細は「 ボブ・ディランの受賞リスト 」を参照

脚注注釈

出典

参考文献

外部リンク

Bob DylanFrom encyclopedia

Bob Dylan (/ˈdɪlən/; born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American songwriter, singer, artist, and writer. He has been influential in popular music and culture for more than five decades. Much of his most celebrated work dates from the 1960s when his songs chronicled social unrest. Early songs such as "Blowin' in the Wind" and "The Times They Are a-Changin'" became anthems for the American civil rights and anti-war movements. Leaving behind his initial base in the American folk music revival, his six-minute single "Like a Rolling Stone", recorded in 1965, enlarged the range of popular music. Dylan's lyrics incorporate a wide range of political, social, philosophical, and literary influences. They defied existing pop music conventions and appealed to the burgeoning counterculture. Initially inspired by the performances of Little Richard and the songwriting of Woody Guthrie, Robert Johnson, and Hank Williams, Dylan has amplified and personalized musical genres. His recording career, spanning more than 50 years, has explored the traditions in American song—from folk, blues, and country to gospel, rock and roll, and rockabilly to English, Scottish, and Irish folk music, embracing even jazz and the Great American Songbook. Dylan performs with guitar, keyboards, and harmonica. Backed by a changing lineup of musicians, he has toured steadily since the late 1980s on what has been dubbed the Never Ending Tour. His accomplishments as a recording artist and performer have been central to his career, but songwriting is considered his greatest contribution. Since 1994, Dylan has published six books of drawings and paintings, and his work has been exhibited in major art galleries. As a musician, Dylan has sold more than 100 million records, making him one of the best-selling artists of all time. He has also received numerous awards including eleven Grammy Awards, a Golden Globe Award, and an Academy Award. Dylan has been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Minnesota Music Hall of Fame, Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, and Songwriters Hall of Fame. The Pulitzer Prize jury in 2008 awarded him a special citation for "his profound impact on popular music and American culture, marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power." In May 2012, Dylan received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama. In October 2016, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first to receive this honor for songwriting. Life and careerOrigins and musical beginningsBob Dylan was born Robert Allen Zimmerman (Hebrew name שבתאי זיסל בן אברהם [Shabtai Zisl ben Avraham])[2][3] in St. Mary's Hospital on May 24, 1941, in Duluth, Minnesota,[4][5] and raised in Hibbing, Minnesota, on the Mesabi Range west of Lake Superior. He has a younger brother, David. Dylan's paternal grandparents, Zigman and Anna Zimmerman, emigrated from Odessa, in the Russian Empire (now Ukraine), to the United States following the anti-Semitic pogroms of 1905.[6] His maternal grandparents, Ben and Florence Stone, were Lithuanian Jews who arrived in the United States in 1902.[6] In his autobiography, Chronicles: Volume One, Dylan wrote that his paternal grandmother's maiden name was Kirghiz and her family originated from Kağızman district of Kars Province in northeastern Turkey.[7] Dylan's parents, Abram Zimmerman and Beatrice "Beatty" Stone, were part of a small, close-knit Jewish community. They lived in Duluth until Robert was six, when his father had polio and the family returned to his mother's hometown, Hibbing, where they lived for the rest of Robert's childhood. In his early years he listened to the radio—first to blues and country stations from Shreveport, Louisiana, and later, when he was a teenager, to rock and roll.[8] He formed several bands while attending Hibbing High School. In the Golden Chords, he performed covers of songs by Little Richard[9] and Elvis Presley.[10] Their performance of Danny & the Juniors' "Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay" at their high school talent show was so loud that the principal cut the microphone.[11] In 1959, his high school yearbook carried the caption "Robert Zimmerman: to join 'Little Richard'."[9][12] The same year, as Elston Gunnn [sic], he performed two dates with Bobby Vee, playing piano and clapping.[13][14][15] Zimmerman moved to Minneapolis in September 1959 and enrolled at the University of Minnesota. His focus on rock and roll gave way to American folk music. In 1985, he said:

He began to perform at the Ten O'Clock Scholar, a coffeehouse a few blocks from campus, and became involved in the Dinkytown folk music circuit.[17][18] During his Dinkytown days, Zimmerman began introducing himself as "Bob Dylan".[19][a 1] In his memoir, Dylan said he hit upon using this less common variant for Dillon – a surname he had considered adopting – when he unexpectedly saw some poems by Dylan Thomas.[20] Explaining his change of name in a 2004 interview, Dylan remarked, "You're born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents. I mean, that happens. You call yourself what you want to call yourself. This is the land of the free."[21] 1960sRelocation to New York and record dealIn May 1960, Dylan dropped out of college at the end of his first year. In January 1961, he traveled to New York City, to perform there and visit his musical idol Woody Guthrie,[22] who was seriously ill with Huntington's disease in Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital.[23] Guthrie had been a revelation to Dylan and influenced his early performances. Describing Guthrie's impact, he wrote: "The songs themselves had the infinite sweep of humanity in them... [He] was the true voice of the American spirit. I said to myself I was going to be Guthrie's greatest disciple."[24] As well as visiting Guthrie in hospital, Dylan befriended Guthrie's acolyte Ramblin' Jack Elliott. Much of Guthrie's repertoire was channeled through Elliott, and Dylan paid tribute to Elliott in Chronicles: Volume One.[25] From February 1961, Dylan played at clubs around Greenwich Village. He befriended and picked up material from folk singers there, including Dave Van Ronk, Fred Neil, Odetta, the New Lost City Ramblers, and Irish musicians the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem.[26] In September, Dylan gained public recognition when Robert Shelton wrote a review in The New York Times of a show at Gerde's Folk City.[27] The same month Dylan played harmonica on folk singer Carolyn Hester's third album, which brought his talents to the attention of the album's producer, John Hammond.[28] Hammond signed Dylan to Columbia Records in October. The performances on his first Columbia album—Bob Dylan—in March 1962,[29] consisted of familiar folk, blues and gospel with two original compositions. The album sold only 5,000 in its first year, just enough to break even.[30] Within Columbia Records, some referred to the singer as "Hammond's Folly"[31] and suggested dropping his contract, but Hammond defended Dylan and was supported by Johnny Cash.[30] In March 1962, Dylan contributed harmonica and back-up vocals to the album Three Kings and the Queen, accompanying Victoria Spivey and Big Joe Williams on a recording for Spivey Records.[32] While working for Columbia, Dylan recorded under the pseudonym Blind Boy Grunt[33] for Broadside, a folk magazine and record label.[34] Dylan used the pseudonym Bob Landy to record as a piano player on The Blues Project, a 1964 anthology album by Elektra Records.[33] As Tedham Porterhouse, Dylan played harmonica on Ramblin' Jack Elliott's 1964 album, Jack Elliott.[33]

Dylan with Joan Baez during the civil rights "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom", August 28, 1963

Dylan made two important career moves in August 1962: he legally changed his name to Robert Dylan,[36] and he signed a management contract with Albert Grossman.[37] (In June 1961, Dylan had signed an agreement with Roy Silver. In 1962, Grossman paid Silver $10,000 to become sole manager.)[38] Grossman remained Dylan's manager until 1970, and was notable for his sometimes confrontational personality and for protective loyalty.[39] Dylan said, "He was kind of like a Colonel Tom Parker figure ... you could smell him coming."[18] Tensions between Grossman and John Hammond led to Hammond's being replaced as producer of Dylan's second album by the young African-American jazz producer, Tom Wilson.[40]

Dylan made his first trip to the United Kingdom from December 1962 to January 1963.[41] He had been invited by TV director Philip Saville to appear in a drama, Madhouse on Castle Street, which Saville was directing for BBC Television.[42] At the end of the play, Dylan performed "Blowin' in the Wind", one of its first public performances.[42] The film recording of Madhouse on Castle Street was destroyed by the BBC in 1968.[42] While in London, Dylan performed at London folk clubs, including the Troubadour, Les Cousins, and Bunjies.[41] He also learned material from UK performers, including Martin Carthy.[42] By the time of Dylan's second album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, in May 1963, he had begun to make his name as a singer and a songwriter. Many songs on this album were labeled protest songs, inspired partly by Guthrie and influenced by Pete Seeger's passion for topical songs.[43] "Oxford Town", for example, was an account of James Meredith's ordeal as the first black student to risk enrollment at the University of Mississippi.[44] The first song on the Freewheelin' album, "Blowin' in the Wind", partly derived its melody from the traditional slave song, "No More Auction Block",[45] while its lyrics questioned the social and political status quo. The song was widely recorded by other artists and became a hit for Peter, Paul and Mary.[46] Another Freewheelin' song, "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" was based on the folk ballad "Lord Randall". With veiled references to an impending apocalypse, the song gained more resonance when the Cuban Missile Crisis developed a few weeks after Dylan began performing it.[47][a 2] Like "Blowin' in the Wind", "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" marked a new direction in songwriting, blending a stream-of-consciousness, imagist lyrical attack with traditional folk form.[48] Dylan's topical songs enhanced his early reputation, and he came to be seen as more than just a songwriter. Janet Maslin wrote of Freewheelin': "These were the songs that established [Dylan] as the voice of his generation—someone who implicitly understood how concerned young Americans felt about nuclear disarmament and the growing movement for civil rights: his mixture of moral authority and nonconformity was perhaps the most timely of his attributes."[49][a 3] Freewheelin' also included love songs and surreal talking blues. Humor was an important part of Dylan's persona,[50] and the range of material on the album impressed listeners, including the Beatles. George Harrison said of the album, "We just played it, just wore it out. The content of the song lyrics and just the attitude—it was incredibly original and wonderful."[51] The rough edge of Dylan's singing was unsettling to some but an attraction to others. Joyce Carol Oates wrote: "When we first heard this raw, very young, and seemingly untrained voice, frankly nasal, as if sandpaper could sing, the effect was dramatic and electrifying."[52] Many early songs reached the public through more palatable versions by other performers, such as Joan Baez, who became Dylan's advocate as well as his lover.[53] Baez was influential in bringing Dylan to prominence by recording several of his early songs and inviting him on stage during her concerts.[54] Others who had hits with Dylan's songs in the early 1960s included the Byrds, Sonny & Cher, the Hollies, Peter, Paul and Mary, the Association, Manfred Mann and the Turtles. Most attempted a pop feel and rhythm, while Dylan and Baez performed them mostly as sparse folk songs. The covers became so ubiquitous that CBS promoted him with the slogan "Nobody Sings Dylan Like Dylan."[55] "Mixed-Up Confusion", recorded during the Freewheelin' sessions with a backing band, was released as a single and then quickly withdrawn. In contrast to the mostly solo acoustic performances on the album, the single showed a willingness to experiment with a rockabilly sound. Cameron Crowe described it as "a fascinating look at a folk artist with his mind wandering towards Elvis Presley and Sun Records."[56] Protest and Another SideIn May 1963, Dylan's political profile rose when he walked out of The Ed Sullivan Show. During rehearsals, Dylan had been told by CBS television's head of program practices that "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues" was potentially libelous to the John Birch Society. Rather than comply with censorship, Dylan refused to appear.[57] By this time, Dylan and Baez were prominent in the civil rights movement, singing together at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963.[58] Dylan's third album, The Times They Are a-Changin', reflected a more politicized and cynical Dylan.[59] The songs often took as their subject matter contemporary stories, with "Only A Pawn In Their Game" addressing the murder of civil rights worker Medgar Evers; and the Brechtian "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" the death of black hotel barmaid Hattie Carroll, at the hands of young white socialite William Zantzinger.[60] On a more general theme, "Ballad of Hollis Brown" and "North Country Blues" addressed despair engendered by the breakdown of farming and mining communities. This political material was accompanied by two personal love songs, "Boots of Spanish Leather" and "One Too Many Mornings".[61] By the end of 1963, Dylan felt both manipulated and constrained by the folk and protest movements.[62] Accepting the "Tom Paine Award" from the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee shortly after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, an intoxicated Dylan questioned the role of the committee, characterized the members as old and balding, and claimed to see something of himself and of every man in Kennedy's assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald.[63]

Bobby Dylan, as the college yearbook lists him: St. Lawrence University, upstate New York, November 1963

In the latter half of 1964 and 1965, Dylan moved from folk songwriter to folk-rock pop-music star. His jeans and work shirts were replaced by a Carnaby Street wardrobe, sunglasses day or night, and pointed "Beatle boots". A London reporter wrote: "Hair that would set the teeth of a comb on edge. A loud shirt that would dim the neon lights of Leicester Square. He looks like an undernourished cockatoo."[69] Dylan began to spar with interviewers. Appearing on the Les Crane television show and asked about a movie he planned, he told Crane it would be a cowboy horror movie. Asked if he played the cowboy, Dylan replied, "No, I play my mother."[70] Going electricMain article: Electric Dylan controversy

Dylan's late March 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home was another leap,[71] featuring his first recordings with electric instruments. The first single, "Subterranean Homesick Blues", owed much to Chuck Berry's "Too Much Monkey Business";[72] its free association lyrics described as harkening back to the energy of beat poetry and as a forerunner of rap and hip-hop.[73] The song was provided with an early video, which opened D. A. Pennebaker's cinéma vérité presentation of Dylan's 1965 tour of Great Britain, Dont Look Back.[74] Instead of miming, Dylan illustrated the lyrics by throwing cue cards containing key words from the song on the ground. Pennebaker said the sequence was Dylan's idea, and it has been imitated in music videos and advertisements.[75] The second side of Bringing It All Back Home contained four long songs on which Dylan accompanied himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica.[76] "Mr. Tambourine Man" became one of his best known songs when the Byrds recorded an electric version that reached number one in the US and UK .[77][78] "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue" and "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" were two of Dylan's most important compositions.[76][79] In 1965, heading the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan performed his first electric set since high school with a pickup group mostly from the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, featuring Mike Bloomfield (guitar), Sam Lay (drums) and Jerome Arnold (bass), plus Al Kooper (organ) and Barry Goldberg (piano).[80] Dylan had appeared at Newport in 1963 and 1964, but in 1965 met with cheering and booing and left the stage after three songs. One version has it that the boos were from folk fans whom Dylan had alienated by appearing, unexpectedly, with an electric guitar. Murray Lerner, who filmed the performance, said: "I absolutely think that they were booing Dylan going electric."[81] An alternative account claims audience members were upset by poor sound and a short set. This account is supported by Kooper and one of the directors of the festival, who reports his recording proves the only boos were in reaction to the MC's announcement that there was only enough time for a short set.[82][83] Nevertheless, Dylan's performance provoked a hostile response from the folk music establishment.[84][85] In the September issue of Sing Out!, Ewan MacColl wrote: "Our traditional songs and ballads are the creations of extraordinarily talented artists working inside disciplines formulated over time ...'But what of Bobby Dylan?' scream the outraged teenagers ... Only a completely non-critical audience, nourished on the watery pap of pop music, could have fallen for such tenth-rate drivel."[86] On July 29, four days after Newport, Dylan was back in the studio in New York, recording "Positively 4th Street". The lyrics contained images of vengeance and paranoia,[87] and it has been interpreted as Dylan's put-down of former friends from the folk community—friends he had known in clubs along West 4th Street.[88] Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on BlondeIn July 1965, the single "Like a Rolling Stone" peaked at two in the U.S. and at four in the UK charts. At over six minutes, the song altered what a pop single could convey. Bruce Springsteen, in his speech for Dylan's inauguration into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, said that on first hearing the single, "that snare shot sounded like somebody'd kicked open the door to your mind".[90] In 2004 and in 2011, Rolling Stone listed it as number one of "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[89][91] The song opened Dylan's next album, Highway 61 Revisited, named after the road that led from Dylan's Minnesota to the musical hotbed of New Orleans.[92] The songs were in the same vein as the hit single, flavored by Mike Bloomfield's blues guitar and Al Kooper's organ riffs. "Desolation Row", backed by acoustic guitar and understated bass,[93] offers the sole exception, with Dylan alluding to figures in Western culture in a song described by Andy Gill as "an 11-minute epic of entropy, which takes the form of a Fellini-esque parade of grotesques and oddities featuring a huge cast of celebrated characters, some historical (Einstein, Nero), some biblical (Noah, Cain and Abel), some fictional (Ophelia, Romeo, Cinderella), some literary (T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound), and some who fit into none of the above categories, notably Dr. Filth and his dubious nurse."[94] In support of the album, Dylan was booked for two U.S. concerts with Al Kooper and Harvey Brooks from his studio crew and Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm, former members of Ronnie Hawkins's backing band the Hawks.[95] On August 28 at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium, the group was heckled by an audience still annoyed by Dylan's electric sound. The band's reception on September 3 at the Hollywood Bowl was more favorable.[96] From September 24, 1965, in Austin, Texas, Dylan toured the U.S. and Canada for six months, backed by the five musicians from the Hawks who became known as the Band.[97] While Dylan and the Hawks met increasingly receptive audiences, their studio efforts floundered. Producer Bob Johnston persuaded Dylan to record in Nashville in February 1966, and surrounded him with top-notch session men. At Dylan's insistence, Robertson and Kooper came from New York City to play on the sessions.[98] The Nashville sessions produced the double album Blonde on Blonde (1966), featuring what Dylan called "that thin wild mercury sound".[99] Kooper described it as "taking two cultures and smashing them together with a huge explosion": the musical world of Nashville and the world of the "quintessential New York hipster" Bob Dylan.[100] On November 22, 1965, Dylan secretly married 25-year-old former model Sara Lownds.[101] Some of Dylan's friends, including Ramblin' Jack Elliott, say that, immediately after the event, Dylan denied he was married.[101] Journalist Nora Ephron made the news public in the New York Post in February 1966 with the headline "Hush! Bob Dylan is wed."[102] Dylan toured Australia and Europe in April and May 1966. Each show was split in two. Dylan performed solo during the first half, accompanying himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica. In the second, backed by the Hawks, he played electrically amplified music. This contrast provoked many fans, who jeered and slow handclapped.[103] The tour culminated in a raucous confrontation between Dylan and his audience at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in England on May 17, 1966.[104] A recording of this concert was released in 1998: The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966. At the climax of the evening, a member of the audience, angered by Dylan's electric backing, shouted: "Judas!" to which Dylan responded, "I don't believe you ... You're a liar!" Dylan turned to his band and said, "Play it fucking loud!"[105] as they launched into the final song of the night—"Like a Rolling Stone". During his 1966 tour, Dylan was described as exhausted and acting "as if on a death trip".[106] D. A. Pennebaker, the film maker accompanying the tour, described Dylan as "taking a lot of amphetamine and who-knows-what-else."[107] In a 1969 interview with Jann Wenner, Dylan said, "I was on the road for almost five years. It wore me down. I was on drugs, a lot of things ... just to keep going, you know?"[108] In 2011, BBC Radio 4 reported that, in an interview that Robert Shelton taped in 1966, Dylan said he had kicked heroin in New York City: "I got very, very strung out for a while ... I had about a $25-a-day habit and I kicked it."[109] Some journalists questioned the validity of this confession, pointing out that Dylan had "been telling journalists wild lies about his past since the earliest days of his career."[110][111] Motorcycle accident and reclusionAfter his tour, Dylan returned to New York, but the pressures increased. ABC Television had paid an advance for a TV show.[112] His publisher, Macmillan, was demanding a manuscript of the poem/novel Tarantula. Manager Albert Grossman had scheduled a concert tour for the latter part of the year. On July 29, 1966, Dylan crashed his 500cc Triumph Tiger 100 motorcycle near his home in Woodstock, New York, and was thrown to the ground. Though the extent of his injuries was never disclosed, Dylan said that he broke several vertebrae in his neck.[113] Mystery still surrounds the circumstances of the accident since no ambulance was called to the scene and Dylan was not hospitalized.[113][114] Dylan's biographers have written that the crash offered Dylan the chance to escape the pressures around him.[113][115] Dylan confirmed this interpretation in his autobiography: "I had been in a motorcycle accident and I'd been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race."[116] Dylan withdrew from public and, apart from a few appearances, did not tour again for almost eight years.[117] Once Dylan was well enough to resume creative work, he began to edit D. A. Pennebaker's film of his 1966 tour. A rough cut was shown to ABC Television and rejected as incomprehensible to a mainstream audience.[118] The film was subsequently titled Eat the Document on bootleg copies, and it has been screened at a handful of film festivals.[119][120] In 1967 he began recording with the Hawks at his home and in the basement of the Hawks' nearby house, "Big Pink".[121] These songs, initially demos for other artists to record, provided hits for Julie Driscoll and the Brian Auger Trinity ("This Wheel's on Fire"), The Byrds ("You Ain't Goin' Nowhere", "Nothing Was Delivered"), and Manfred Mann ("Mighty Quinn"). Columbia released selections in 1975 as The Basement Tapes. Over the years, more songs recorded by Dylan and his band in 1967 appeared on bootleg recordings, culminating in a five-CD set titled The Genuine Basement Tapes, containing 107 songs and alternative takes.[122] In the coming months, the Hawks recorded the album Music from Big Pink using songs they worked on in their basement in Woodstock, and renamed themselves the Band,[123] beginning a long recording and performing career of their own. In October and November 1967, Dylan returned to Nashville.[124] Back in the studio after 19 months, he was accompanied by Charlie McCoy on bass,[124] Kenny Buttrey on drums,[124] and Pete Drake on steel guitar.[124] The result was John Wesley Harding, a contemplative record of shorter songs, set in a landscape that drew on the American West and the Bible. The sparse structure and instrumentation, with lyrics that took the Judeo-Christian tradition seriously, departed from Dylan's own work and from the psychedelic fervor of the 1960s.[125] It included "All Along the Watchtower", with lyrics derived from the Book of Isaiah (21:5–9). The song was later recorded by Jimi Hendrix, whose version Dylan acknowledged as definitive.[16] Woody Guthrie died on October 3, 1967, and Dylan made his first live appearance in twenty months at a Guthrie memorial concert held at Carnegie Hall on January 20, 1968, where he was backed by the Band.[126] Dylan's next release, Nashville Skyline (1969), was mainstream country featuring Nashville musicians, a mellow-voiced Dylan, a duet with Johnny Cash, and the hit single "Lay Lady Lay".[128] Variety wrote, "Dylan is definitely doing something that can be called singing. Somehow he has managed to add an octave to his range."[129] Dylan and Cash also recorded a series of duets, but only their recording of Dylan's "Girl from the North Country" was used on the album. In May 1969, Dylan appeared on the first episode of Johnny Cash's television show, duetting with Cash on "Girl from the North Country", "I Threw It All Away", and "Living the Blues". Dylan next traveled to England to top the bill at the Isle of Wight festival on August 31, 1969, after rejecting overtures to appear at the Woodstock Festival closer to his home.[130] 1970sIn the early 1970s, critics charged that Dylan's output was varied and unpredictable. Rolling Stone writer Greil Marcus asked "What is this shit?" on first listening to Self Portrait, released in June 1970.[131][132] It was a double LP including few original songs, and was poorly received.[133] In October 1970, Dylan released New Morning, considered a return to form.[134] This album included "Day of the Locusts", a song in which Dylan gave an account of receiving an honorary degree from Princeton University on June 9, 1970.[135] In November 1968, Dylan had co-written "I'd Have You Anytime" with George Harrison;[136] Harrison recorded "I'd Have You Anytime" and Dylan's "If Not for You" for his 1970 solo triple album All Things Must Pass. Dylan's surprise appearance at Harrison's 1971 Concert for Bangladesh attracted media coverage, reflecting that Dylan's live appearances had become rare.[137] Between March 16 and 19, 1971, Dylan reserved three days at Blue Rock, a small studio in Greenwich Village to record with Leon Russell. These sessions resulted in "Watching the River Flow" and a new recording of "When I Paint My Masterpiece".[138] On November 4, 1971, Dylan recorded "George Jackson", which he released a week later. For many, the single was a surprising return to protest material, mourning the killing of Black Panther George Jackson in San Quentin State Prison that year.[139] Dylan contributed piano and harmony to Steve Goodman's album, Somebody Else's Troubles, under the pseudonym Robert Milkwood Thomas (referencing the play Under Milk Wood by Dylan Thomas and his own previous name) in September 1972.[140] In 1972, Dylan signed to Sam Peckinpah's film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, providing songs and backing music for the movie, and playing "Alias", a member of Billy's gang with some historical basis.[141] Despite the film's failure at the box office, the song "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" became one of Dylan's most covered songs.[142][143] Return to touring

Bob Dylan and the Band touring in Chicago, 1974

Dylan began 1973 by signing with a new label, David Geffen's Asylum Records (and Island in the UK), when his contract with Columbia Records expired. On his next album, Planet Waves, he used the Band as backing group, while rehearsing for a tour. The album included two versions of "Forever Young", which became one of his most popular songs.[144] As one critic described it, the song projected "something hymnal and heartfelt that spoke of the father in Dylan",[145] and Dylan himself commented: "I wrote it thinking about one of my boys and not wanting to be too sentimental."[16] Columbia Records simultaneously released Dylan, a collection of studio outtakes (almost exclusively covers), widely interpreted as a churlish response to Dylan's signing with a rival record label.[146] In January 1974, Dylan returned to touring after seven years; backed by the Band, he embarked on a North American tour of 40 concerts. A live double album, Before the Flood, was on Asylum Records. Soon, according to Clive Davis, Columbia Records sent word they "will spare nothing to bring Dylan back into the fold".[147] Dylan had second thoughts about Asylum, miffed that while there had been millions of unfulfilled ticket requests for the 1974 tour, Geffen had sold only 700,000 copies of Planet Waves.[147] Dylan returned to Columbia Records, which reissued his two Asylum albums. After the tour, Dylan and his wife became estranged. He filled a small red notebook with songs about relationships and ruptures, and recorded an album entitled Blood on the Tracks in September 1974.[148] Dylan delayed the release and re-recorded half the songs at Sound 80 Studios in Minneapolis with production assistance from his brother, David Zimmerman.[149] Released in early 1975, Blood on the Tracks received mixed reviews. In the NME, Nick Kent described "the accompaniments [as] often so trashy they sound like mere practice takes."[150] In Rolling Stone, Jon Landau wrote that "the record has been made with typical shoddiness."[150] Over the years critics came to see it as one of Dylan's greatest achievements. In Salon.com, Bill Wyman wrote: "Blood on the Tracks is his only flawless album and his best produced; the songs, each of them, are constructed in disciplined fashion. It is his kindest album and most dismayed, and seems in hindsight to have achieved a sublime balance between the logorrhea-plagued excesses of his mid-1960s output and the self-consciously simple compositions of his post-accident years."[151] Novelist Rick Moody called it "the truest, most honest account of a love affair from tip to stern ever put down on magnetic tape."[152] In the middle of that year, Dylan wrote a ballad championing boxer Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, imprisoned for a triple murder in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1966. After visiting Carter in jail, Dylan wrote "Hurricane", presenting the case for Carter's innocence. Despite its length—over eight minutes—the song was released as a single, peaking at 33 on the U.S. Billboard chart, and performed at every 1975 date of Dylan's next tour, the Rolling Thunder Revue.[a 4][153] The tour featured about one hundred performers and supporters from the Greenwich Village folk scene, including T-Bone Burnett, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Joni Mitchell,[154][155] David Mansfield, Roger McGuinn, Mick Ronson, Joan Baez, and Scarlet Rivera, whom Dylan discovered walking down the street, her violin case on her back.[156] Allen Ginsberg accompanied the troupe, staging scenes for the film Dylan was shooting. Sam Shepard was hired to write the screenplay, but ended up accompanying the tour as informal chronicler.[157] Running through late 1975 and again through early 1976, the tour encompassed the release of the album Desire, with many of Dylan's new songs featuring a travelogue-like narrative style, showing the influence of his new collaborator, playwright Jacques Levy.[158][159] The 1976 half of the tour was documented by a TV concert special, Hard Rain, and the LP Hard Rain; no concert album from the better-received and better-known opening half of the tour was released until 2002's Live 1975.[160] The 1975 tour with the Revue provided the backdrop to Dylan's nearly four-hour film Renaldo and Clara, a sprawling narrative mixed with concert footage and reminiscences. Released in 1978, the movie received poor, sometimes scathing, reviews.[161][162] Later in that year, a two-hour edit, dominated by the concert performances, was more widely released.[163] In November 1976, Dylan appeared at the Band's "farewell" concert, with Eric Clapton, Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison and Neil Young. Martin Scorsese's cinematic chronicle, The Last Waltz, in 1978 included about half of Dylan's set.[164] In 1976, Dylan wrote and duetted on "Sign Language" for Eric Clapton's No Reason To Cry.[165] In 1978, Dylan embarked on a year-long world tour, performing 114 shows in Japan, the Far East, Europe and the US, to a total audience of two million. Dylan assembled an eight piece band and three backing singers. Concerts in Tokyo in February and March were released as the live double album, Bob Dylan At Budokan.[166] Reviews were mixed. Robert Christgau awarded the album a C+ rating, giving the album a derisory review,[167] while Janet Maslin defended it in Rolling Stone, writing: "These latest live versions of his old songs have the effect of liberating Bob Dylan from the originals."[168] When Dylan brought the tour to the U.S. in September 1978, the press described the look and sound as a 'Las Vegas Tour'.[169] The 1978 tour grossed more than $20 million, and Dylan told the Los Angeles Times that he had debts because "I had a couple of bad years. I put a lot of money into the movie, built a big house ... and it costs a lot to get divorced in California."[166] In April and May 1978, Dylan took the same band and vocalists into Rundown Studios in Santa Monica, California, to record an album of new material: Street-Legal.[170] It was described by Michael Gray as, "after Blood On The Tracks, arguably Dylan's best record of the 1970s: a crucial album documenting a crucial period in Dylan's own life".[171] However, it had poor sound and mixing (attributed to Dylan's studio practices), muddying the instrumental detail until a remastered CD release in 1999 restored some of the songs' strengths.[172] Christian periodFurther information: Slow Train Coming

In the late 1970s, Dylan became a born again Christian[173][174][175] and released two albums of contemporary gospel music. Slow Train Coming (1979) featured the guitar accompaniment of Mark Knopfler (of Dire Straits) and was produced by veteran R&B producer Jerry Wexler. Wexler said that Dylan had tried to evangelize him during the recording. He replied: "Bob, you're dealing with a 62-year-old Jewish atheist. Let's just make an album."[176] Dylan won the Grammy Award for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance for the song "Gotta Serve Somebody". His second Christian-themed album, Saved (1980), received mixed reviews, described by Michael Gray as "the nearest thing to a follow-up album Dylan has ever made, Slow Train Coming II and inferior"[177] When touring in late 1979 and early 1980, Dylan would not play his older, secular works, and he delivered declarations of his faith from the stage, such as:

Dylan's Christianity was unpopular with some fans and musicians.[179] Shortly before his murder, John Lennon recorded "Serve Yourself" in response to Dylan's "Gotta Serve Somebody".[180] By 1981, Stephen Holden wrote in the New York Times that "neither age (he's now 40) nor his much-publicized conversion to born-again Christianity has altered his essentially iconoclastic temperament."[181] 1980sIn late 1980, Dylan briefly played concerts billed as "A Musical Retrospective", restoring popular 1960s songs to the repertoire. Shot of Love, recorded early the next year, featured his first secular compositions in more than two years, mixed with Christian songs. "Every Grain of Sand" reminded some of William Blake's verses.[182] In the 1980s, reception of Dylan's recordings varied, from the well-regarded Infidels in 1983 to the panned Down in the Groove in 1988. Michael Gray condemned Dylan's 1980s albums for carelessness in the studio and for failing to release his best songs.[183] As an example of the latter, the Infidels recording sessions, which again employed Knopfler on lead guitar and also as the album's producer, resulted in several notable songs that Dylan left off the album. Best regarded of these were "Blind Willie McTell", a tribute to the dead blues musician and an evocation of African American history,[184] "Foot of Pride" and "Lord Protect My Child". These three songs were released on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961–1991.[185] Between July 1984 and March 1985, Dylan recorded Empire Burlesque.[186] Arthur Baker, who had remixed hits for Bruce Springsteen and Cyndi Lauper, was asked to engineer and mix the album. Baker said he felt he was hired to make Dylan's album sound "a little bit more contemporary".[186] Dylan sang on USA for Africa's famine relief single "We Are the World". On July 13, 1985, he appeared at the climax at the Live Aid concert at JFK Stadium, Philadelphia. Backed by Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood, he performed a ragged version of "Hollis Brown", his ballad of rural poverty, and then said to the worldwide audience exceeding one billion people: "I hope that some of the money ... maybe they can just take a little bit of it, maybe ... one or two million, maybe ... and use it to pay the mortgages on some of the farms and, the farmers here, owe to the banks."[187] His remarks were widely criticized as inappropriate, but they did inspire Willie Nelson to organize a series of events, Farm Aid, to benefit debt-ridden American farmers.[188] In April 1986, Dylan made a foray into rap music when he added vocals to the opening verse of "Street Rock", featured on Kurtis Blow's album Kingdom Blow.[189] Dylan's next studio album, Knocked Out Loaded, in July 1986 contained three covers (by Little Junior Parker, Kris Kristofferson and the gospel hymn "Precious Memories"), plus three collaborations with (Tom Petty, Sam Shepard and Carole Bayer Sager), and two solo compositions by Dylan. One reviewer commented that "the record follows too many detours to be consistently compelling, and some of those detours wind down roads that are indisputably dead ends. By 1986, such uneven records weren't entirely unexpected by Dylan, but that didn't make them any less frustrating."[190] It was the first Dylan album since Freewheelin' (1963) to fail to make the Top 50.[191] Since then, some critics have called the 11-minute epic that Dylan co-wrote with Sam Shepard, "Brownsville Girl", a work of genius.[192] In 1986 and 1987, Dylan toured with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, sharing vocals with Petty on several songs each night. Dylan also toured with the Grateful Dead in 1987, resulting in a live album Dylan & The Dead. This received negative reviews: Allmusic said, "Quite possibly the worst album by either Bob Dylan or the Grateful Dead."[193] Dylan then initiated what came to be called the Never Ending Tour on June 7, 1988, performing with a back-up band featuring guitarist G. E. Smith. Dylan continued to tour with a small, evolving band for the next 20 years.[194]

Dylan in Barcelona, Spain, 1984

In 1987, Dylan starred in Richard Marquand's movie Hearts of Fire, in which he played Billy Parker, a washed-up rock star turned chicken farmer whose teenage lover (Fiona) leaves him for a jaded English synth-pop sensation played by Rupert Everett.[195] Dylan also contributed two original songs to the soundtrack—"Night After Night", and "I Had a Dream About You, Baby", as well as a cover of John Hiatt's "The Usual". The film was a critical and commercial flop.[196] Dylan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in January 1988, with Bruce Springsteen's introduction declaring, "Bob freed your mind the way Elvis freed your body. He showed us that just because music was innately physical did not mean that it was anti-intellectual."[197] The album Down in the Groove in May 1988 sold even more unsuccessfully than his previous studio album.[198] Michael Gray wrote: "The very title undercuts any idea that inspired work may lie within. Here was a further devaluing of the notion of a new Bob Dylan album as something significant."[199] The critical and commercial disappointment of that album was swiftly followed by the success of the Traveling Wilburys. Dylan co-founded the band with George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison, and Tom Petty, and in late 1988 their multi-platinum Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 reached three on the US album chart,[198] featuring songs that were described as Dylan's most accessible compositions in years.[200] Despite Orbison's death in December 1988, the remaining four recorded a second album in May 1990 with the title Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3.[201] Dylan finished the decade on a critical high note with Oh Mercy produced by Daniel Lanois. Michael Gray wrote that the album was: "Attentively written, vocally distinctive, musically warm, and uncompromisingly professional, this cohesive whole is the nearest thing to a great Bob Dylan album in the 1980s."[199][202] The track "Most of the Time", a lost love composition, was later prominently featured in the film High Fidelity, while "What Was It You Wanted?" has been interpreted both as a catechism and a wry comment on the expectations of critics and fans.[203] The religious imagery of "Ring Them Bells" struck some critics as a re-affirmation of faith.[204] 1990sDylan's 1990s began with Under the Red Sky (1990), an about-face from the serious Oh Mercy. The album contained several apparently simple songs, including "Under the Red Sky" and "Wiggle Wiggle". The album was dedicated to "Gabby Goo Goo", a nickname for the daughter of Dylan and Carolyn Dennis, Desiree Gabrielle Dennis-Dylan, who was four.[205] Sidemen on the album included George Harrison, Slash from Guns N' Roses, David Crosby, Bruce Hornsby, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Elton John. Despite the line-up, the record received bad reviews and sold poorly.[206] In 1991, Dylan received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award from American actor Jack Nicholson.[207] The event coincided with the start of the Gulf War against Saddam Hussein, and Dylan performed "Masters of War". Dylan then made a short speech, saying "My daddy once said to me, he said, 'Son, it is possible for you to become so defiled in this world that your own mother and father will abandon you. If that happens, God will believe in your ability to mend your own ways.'"[208] This sentiment was subsequently revealed to be a quote from 19th-century German Jewish intellectual, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch.[209] Over the next few years Dylan returned to his roots with two albums covering folk and blues numbers: Good as I Been to You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993), featuring interpretations and acoustic guitar work. Many critics and fans commented on the quiet beauty of the song "Lone Pilgrim",[210] written by a 19th-century teacher. In November 1994 Dylan recorded two live shows for MTV Unplugged. He said his wish to perform traditional songs was overruled by Sony executives who insisted on hits.[211] The album from it, MTV Unplugged, included "John Brown", an unreleased 1962 song of how enthusiasm for war ends in mutilation and disillusionment.[212]

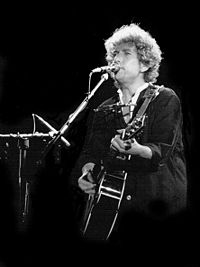

Dylan performs during the 1996 Lida Festival in Stockholm